The HyperTexts

Early Poems: The Best Juvenilia by Poets with Examples

The Best Poems by Child Poets and Teenage Poets

Definition of Juvenilia: In classical antiquity, the Juvenalia, or Ludi Juvenales, were games instituted by the Roman Emperor Nero in 59 AD to commemorate his first

shaving of his beard at age 21. For our purposes, we will define "juvenilia" as works by human beings in their early twenties, or younger. Our focus is on poetry. What follows are the best

early poems that I have come across, to date, plus a few that I have published myself over the last 20+ years, as founder and editor of The HyperTexts.

Famous juvenile writers include Jane Austen, Elizabeth Barrett

Browning, Anne Bronte, Charlotte Bronte, Emily Bronte, Robert Burns, George

Gordon (Lord Byron), Lewis Carroll, Thomas Chatterton, John Clare, Samuel Taylor

Coleridge, William Congreve, Abraham Cowley, William Cowper, e. e. cummings, Digby Dolben,

John Dryden, Arthur Henry Hallam, Felicia Hemans, Leigh Hunt, John Keats, John

Milton, Thomas Moore, Edgar Allan Poe, Alexander Pope, Christina Rossetti,

Robert Southey, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Alfred Tennyson

(Lord Tennyson) and William Wordsworth.

It bears mentioning, I believe, that many of the juvenile poets above―indeed,

most of them―may be deemed Romantics. Furthermore, all the poets I

consider to

be the best poets of the Romantic era―William Blake, Robert

Burns, Lord Byron, Thomas Chatterton, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Percy

Bysshe Shelley and William Wordsworth―wrote publishable poems in their youth.

compiled by Michael

R. Burch

Juvenilia Timeline/Ageline of Famous Poets, Writers and

Songwriters

Marjorie Fleming learned to read at age three―preferring adult books―and died at

age eight; Robert Louis Stevenson called her "the noblest work of God."

She is also known as Marjory Fleming. She was a good and highly original writer

as a child, although her spelling and punctuation could be "eclectic."

I love the morning's sun to spy

Glittering through the casement's eye.

—Marjorie Fleming

Mattie Stepanek wrote his first poem at age three and published six volumes of

poetry called "Heartsongs" before dying at age thirteen.

When I die, I want to be a child in heaven.

I want to be a 10-year-old cherub.

I want to be a hero in heaven & a peacemaker,

just like my goal on earth.

—Mattie J.T. Stepanek

Marshall Ball wrote his first poem, "Altogether Lovely," at age five despite

being unable to speak or move his hands; he "wrote" by looking at alphabet

blocks that his parents assembled into words, then poems.

I love seeing Grandmother.

Her golden pleasant smile touches,

like the wings of a bird,

the ramparts of my mind.

—Marshall Ball

At age six, Edward Estlin Cummings, better known as e. e. cummings, wrote a poem for his father; by age eight he was writing poetry on a daily basis.

FATHER DEAR. BE, YOUR FATHER-GOOD AND GOOD,

HE IS GOOD NOW, IT IS NOT GOOD TO SEE IT RAIN,

FATHER DEAR IS, IT, DEAR, NO FATHER DEAR,

LOVE, YOU DEAR,

ESTLIN.

Elizabeth Barrett (later Browning), wrote her first poem at age six and had her

first collection of poems published at age fourteen. Her future

husband, Robert Browning, is also on this list. She is best known for the sonnet

"How Do I Love Thee (Let Me Count the Ways)" from her collection Sonnets

from the Portuguese. This excerpt is from a long poem, "The Battle of

Marathon," that she apparently wrote some time before her fourteenth birthday.

"Die! thy base shade to gloomy regions fled,

Join there, the shivering phantoms of the dead.

Base slave, return to dust!"

—Elizabeth Barrett (Browning)

Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote "Verses on a Cat" at age eight. His future

wife, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, the author of the famous gothic science

fiction novel, Frankenstein, is also on this list. Percy Shelley's

early poems were collected in The Esdaile Notebook, which was published

in 1961 by Oxford University Press in England and by Harvard University Press in

the United States. The original notebook contained 57 poems occupying 189 pages.

The poems were apparently written from age sixteen to age twenty. This excerpt

was written as a disaffected Shelley left London for Wales:

Let me forever be what I have been,

But not forever at my needy door

Let Misery linger, speechless, pale and lean.

I am the friend of the unfriended poor;

Let me not madly stain their righteous cause in gore.

—Percy Bysshe Shelley

Richard Wilbur, a future American poet laureate, published his first poem at age

eight, in John Martin's Magazine.

A. E. Housman began writing poetry at age eight.

James Baldwin wrote his first play at age nine.

Around age ten, Thomas Chatterton wrote his first published poem, "On the Last

Epiphany, or, Christ Coming to Judgment." The short poem "Bristol" was

written when Chatterton was sixteen:

The Muses have no Credit here; and Fame

Confines itself to the mercantile name.

Bristol may keep her prudent maxims still;

I scorn her Prudence, and I ever will.

Since all my vices magnify'd are here,

She cannot paint me worse than I appear.

When raving in the lunacy of ink,

I catch the Pen and publish what I think.

—Thomas Chatterton

At age ten, Alfred Tennyson was writing "hundreds and

hundreds of lines in regular Popeian metre."

Heavily hangs the broad sunflower

Over its grave i' the earth so chilly;

Heavily hangs the hollyhock,

Heavily hangs the tiger-lily.

—Alfred Tennyson

Helen Keller, despite being blind, deaf and unable to speak until age six, wrote a

short story, "The Frost King," that was published by age eleven.

Stevie Wonder wrote his first song, "Lonely Boy," at age eleven.

Oscar Wilde may have begun writing "Requiescat," his wonderful elegy to his

sister Isola, around age twelve; he published a number of poems in his teens.

Lily-like, white as snow,

She hardly knew

She was a woman, so

Sweetly she grew.

—Oscar Wilde

On a personal note, I read the Bible from cover to cover around age ten or

eleven. Sometime after reading the Bible, between the ages of 11 and 13, I came up with the following epigram:

If God

is good,

half the Bible

is libel.

—Michael

R. Burch

Alexander Pope wrote his famous poem "Ode to Solitude" at age twelve.

Christina Rossetti began to record the dates of her poems

at age twelve.

Robert Browning's parents attempted to publish a book of his poems,

Incondita, when he was age twelve. He would later destroy the manuscript.

Paul Simon wrote his first song, "The Girl for Me," at age twelve.

Anne Frank started her famous diary at age thirteen.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge started writing his monody to Thomas Chatterton at age

thirteen.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published his first poem in the

Portland Gazette at age thirteen, "The Battle of Lovell's Pond."

William Cullen Bryant had a satirical poem "The Embargo" published at age

thirteen.

Lord Byron had poems written at age fourteen published in

Fugitive Pieces, but the book was recalled and burned because some of the

poems were too "hot"!

Edgar Allan Poe is writing poems to woo girls at age fourteen; he writes "To

Helen" around age fifteen after being inspired by the slender, graceful figure

of a friend's mother!

Stephen Crane wrote the short story "Uncle Jake and the Bell Handle" at age

fourteen.

Arthur Rimbaud was published at age fifteen; he retired

from writing at age nineteen to become a soldier and smuggler!

Robert Burns, generally considered to be the greatest of the Scottish bards,

wrote a love poem at age fifteen.

According to Thomas Seccombe, William Blake's "How Sweet I Roamed" was written

around age fifteen.

W. H. Auden began writing poems at age fifteen.

Philip Larkin began writing poems around the same age, and Auden was one of his

early influences!

Taylor Swift wrote her song "Love Story" at age sixteen.

Lorde wrote her song "Royals" with its "different kind of buzz" at age sixteen.

George Michael wrote the song "Careless Whisper" at age seventeen.

S. E. Hinton wrote her first book at age fifteen and published her best-selling

novel The Outsiders at age eighteen.

Alfred Tennyson and his two elder brothers had a book of poems published when he

was seventeen.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, the wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley, began work on her famous

gothic horror novel Frankenstein at age eighteen, while they were

visiting Lord Byron. All three are on this list.

Alicia Keys wrote her stunning debut single and smash hit "Fallin'" at age

twenty.

NOTE: In the list above the term "first poem" means the first poem that we are

aware of, which is not necessarily the first poem written. The first poem of

mine that I have in my possession dates to when I was fourteen years old. But I

remember writing a small number of poems at much younger ages: some as school

assignments, others as larks. However, I didn't keep the poems and can't

remember anything about them, except that one may have been about ants, a hill,

or an anthill. So for all practical purposes, my career as a poet begins with

the first "serious" poems that I can produce. And I was

dead serious about becoming a poet by age fifteen. (Whether I succeeded may

still be open to debate, but I'm working on it!)―Michael R. Burch

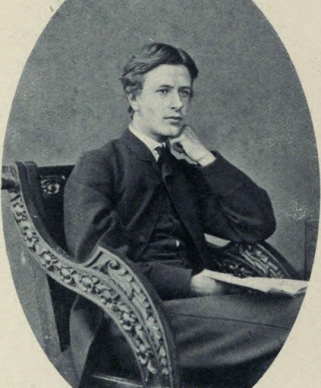

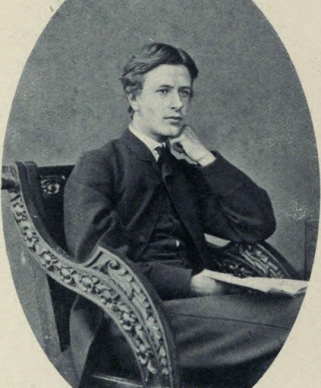

A Song

by Digby Mackworth Dolben

Digby Dolben (1848-1867) died at age nineteen, so all his poems were written in

his teens. While he has been largely if not completely forgotten, a book of his

poems was edited and published by Robert Bridges, an English poet laureate, so

his poetry fortunately survives. In my opinion, Digby Dolben is a poet who

deserves to be read. The poem below is one shining example.

The world is young today:

Forget the gods are old,

Forget the years of gold

When all the months were May.

A little flower of Love

Is ours, without a root,

Without the end of fruit,

Yet – take the scent thereof.

There may be hope above,

There may be rest beneath;

We see them not, but Death

Is palpable – and Love.

For a brief bio of Digby Dolben by Simon Edge, please click here:

Digby Dolben Bio.

To read more of his work please click

The Best Poems of Digby Mackworth Dolben.

Song from Ælla: Under the Willow Tree, or, Minstrel's Song

by Thomas Chatterton, age 17 or younger

modernization/translation by

Michael R. Burch

O! sing unto my roundelay,

O! drop the briny tear with me,

Dance no more at holy-day,

Like a running river be:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Black his crown as the winter night,

White his flesh as the summer snow

Red his face as the morning light,

Cold he lies in the grave below:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Sweet his tongue as the throstle's note,

Quick in dance as thought can be,

Deft his tabor, cudgel stout;

O! he lies by the willow-tree!

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Hark! the raven flaps his wing

In the briar'd dell below;

Hark! the death-owl loud doth sing

To the nightmares, as they go:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

See! the white moon shines on high;

Whiter is my true-love's shroud:

Whiter than the morning sky,

Whiter than the evening cloud:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Here upon my true-love's grave

Shall the barren flowers be laid;

Not one holy saint to save

All the coldness of a maid:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

With my hands I'll frame the briars

Round his holy corpse to grow:

Elf and fairy, light your fires,

Here my body, stilled, shall go:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Come, with acorn-cup and thorn,

Drain my heartès blood away;

Life and all its good I scorn,

Dance by night, or feast by day:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Water witches, crowned with plaits,

Bear me to your lethal tide.

I die; I come; my true love waits.

Thus the damsel spoke, and died.

The song above is, in my opinion, competitive with Shakespeare's

songs in his plays, and may be the best of Thomas Chatterton's so-called "Rowley" poems. It seems

rather obvious that this song was written in modern English, then "backdated."

One wonders whether Chatterton wrote it in response to Shakespeare's "Under the

Greenwood Tree." The greenwood tree or evergreen is a symbol of immortality. The

"weeping willow" is a symbol of sorrow, and the greatest human sorrow is that of

mortality and the separations caused by death. If Chatterton wrote his song as a

refutation of Shakespeare's, I think he did a damn good job. But it's a splendid

song in its own right.

Song

by Alfred Tennyson

This poem was first printed in 1830, when Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) was around

twenty years old. From what I have been able to gather, the poem

was written in the garden at the Old Rectory, Somersby, where his father was the

rector. Tennyson and his two elder brothers had a book of poems published when

Alfred was seventeen. This poem seems to have

haunted Edgar Allan Poe, a fervent admirer of Tennyson's early poems.

1.

A Spirit haunts the year's last hours

Dwelling amid these yellowing bowers:

To himself he talks;

For at eventide, listening earnestly,

At his work you may hear him sob and sigh

In the walks;

Earthward he boweth the heavy stalks

Of the mouldering flowers:

Heavily hangs the broad sunflower

Over its grave i' the earth so chilly;

Heavily hangs the hollyhock,

Heavily hangs the tiger-lily.

2.

The air is damp, and hush'd, and close,

As a sick man's room when he taketh repose

An hour before death;

My very heart faints and my whole soul grieves

At the moist rich smell of the rotting leaves,

And the breath

Of the fading edges of box beneath,

And the year's last rose.

Heavily hangs the broad sunflower

Over its grave i' the earth so chilly;

Heavily hangs the hollyhock,

Heavily hangs the tiger-lily.

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde was born in Dublin in 1854. In 1867, Oscar

Wilde's sister Isola died at age nine; he was twelve at the time. His elegy for

Isola, "Requiescat," is surely one of the loveliest and most touching poems in

the English language. According to poeticus.com, Wilde wrote the poem in his

teens. If so it is certainly a contender for the mantle of the best poem by a

teenage poet! Wilde attached the word "Avignon" to the poem; according to

Victorian Literature: An Anthology, Wilde is believed to have visited

Avignon in 1875 and to have finished the poem there. In any case, at age

seventeen he was awarded a royal scholarship to read classics at Trinity

College, Dublin, where he shared rooms with his older brother Willie Wilde (who

also became a published poet). At Trinity, Oscar Wilde worked with his tutor, J.

P. Mahaffy, on the latter's book Social Life in Greece. Mahaffy at one

time boasted of having created Wilde; later, he named him "the only blot on my

tutorship." Wilde became an established member of the University Philosophical

Society: "the members' suggestion book for 1874 contains two pages of banter

(sportingly) mocking Wilde's emergent aestheticism." Around that time Wilde

presented a paper titled "Aesthetic Morality," which may be his first datable

prose work. His first datable poem may be "Arona" which bears the timestamp July

10, 1875. "A Chorus of Cloud Maidens," Wilde’s earliest published poem, appeared

in the Dublin University Magazine in November 1875, and was signed

Oscar O’F. Wills Wilde. By 1876, Wilde had been published in literary magazines

such as The Irish Monthly, Month, Charmides and Kottabos. (In

the Month, Wilde was identified only by his unusual initials: OFO’FWW.

And ironically, while accepting the hedonistic Wilde, who lived up to his last

name, the Jesuit magazine turned down one of its own, Father Gerard Manley

Hopkins!) At Trinity, Wilde established himself as an outstanding student: he

came first in his class in his first year, won a scholarship by competitive

examination in his second, and then, in his finals, won the Berkeley Gold Medal,

the University's highest academic award in Greek. He was encouraged to compete

for a demyship (scolarship) to Magdalen College, Oxford, which he won easily, having already

studied Greek for over nine years. In 1878, the year of his graduation, his poem

"Ravenna" won the Newdigate Prize for the best English verse composition by an

Oxford undergraduate. So either by his teens, or no later than his early

twenties, Wilde was an accomplished poet and he would go on to become an

important playwright, novelist and epigrammatist.

There’s also a description of Oscar in adulthood, recalling his sister Isola

“dancing like a golden sunbeam about the house.” In Wilde’s poem "Requiescat" his love for her is palpable:

Requiescat

by Oscar Wilde

Tread lightly, she is near

Under the snow,

Speak gently, she can hear

The daisies grow.

All her bright golden hair

Tarnished with rust,

She that was young and fair

Fallen to dust.

Lily-like, white as snow,

She hardly knew

She was a woman, so

Sweetly she grew.

Coffin-board, heavy stone,

Lie on her breast,

I vex my heart alone,

She is at rest.

Peace, Peace, she cannot hear

Lyre or sonnet,

All my life's buried here,

Heap earth upon it.

Below, the original poem appears on the left. My

translation/modernization on the right can be used as a reference or study

guide. If you prefer not to wrestle with the medieval spellings, you can start

with the translation and refer back to the original poem as you prefer. Please

keep in mind that translating or "modernizing" such a poem is far from a perfect

science. Concessions must be made to meter, if the poem is to remain rhythmic; this means sometimes adding a word here and deleting a word there,

hopefully without altering the poet's intended meaning. Chatterton is

difficult to interpret, in spots, because it seems likely that he coined words

to suit his meter and purpose. While there is nothing "wrong" with that

(Shakespeare did the same), it is not always completely obvious what Chatterton

meant. I have tried to remain faithful to what I interpret as his "larger"

meaning. ― Michael R. Burch

An Excelente Balade of Charitie An Excellent Ballad of Charity

by Thomas Chatterton, age 17 by Thomas Chatterton, age 17

Original Version Modernization/Translation by

Michael R. Burch

As wroten bie the goode Prieste

Thomas Rowley 1464

In Virgynë the sweltrie sun gan sheene, In Virgynë the swelt'ring sun grew keen,

And hotte upon the mees did caste his raie;

Then hot upon the meadows cast his ray;

The apple rodded from its palie greene, The apple ruddied

from its pallid green

And the mole peare did bende the leafy spraie; And the fat pear did bend its leafy spray;

The peede chelandri sunge the livelong daie; The pied goldfinches sang

the livelong day;

’Twas nowe the pride, the manhode of the yeare, 'Twas now the pride, the manhood of the year,

And eke the grounde was dighte in its moste And the ground was mantled in fine green cashmere.

defte aumere.

The sun was glemeing in the midde of daie, The sun was gleaming in the bright mid-day,

Deadde still the aire, and eke the welken blue, Dead-still the air, and likewise the heavens blue,

When from the sea arist in drear arraie When from the sea arose, in drear array,

A hepe of cloudes of sable sullen hue, A heap of clouds of sullen sable hue,

The which full fast unto the woodlande drewe, Which full and fast unto the woodlands drew,

Hiltring attenes the sunnis fetive face, Hiding at once the sun's fair festive face,

And the blacke tempeste swolne and gatherd As the black tempest swelled and gathered up apace.

up apace.

Beneathe an holme, faste by a pathwaie side, Beneath a holly tree, by a pathway's side,

Which dide unto Seyncte Godwine’s covent lede, Which did unto Saint Godwin's convent lead,

A hapless pilgrim moneynge did abide. A hapless pilgrim moaning did abide.

Pore in his newe, ungentle in his weede,

Poor in his sight, ungentle in his weed,

Longe bretful of the miseries of neede,

Long brimful of the miseries of need,

Where from the hail-stone coulde the almer flie? Where from the hailstones could the

beggar fly?

He had no housen theere, ne anie covent nie. He had no shelter there, nor any convent nigh.

Look in his glommed face, his sprighte there scanne; Look in his gloomy face; his sprite there scan;

Howe woe-be-gone, how withered, forwynd, deade! How woebegone, how withered, dried-up, dead!

Haste to thie church-glebe-house, asshrewed manne! Haste to thy

parsonage, accursèd man!

Haste to thie kiste, thie onlie dortoure bedde. Haste to thy crypt, thy only restful bed.

Cale, as the claie whiche will gre on thie hedde, Cold, as the clay which will grow on thy head,

Is Charitie and Love aminge highe elves; Is Charity and Love among high elves;

Knightis and Barons live for pleasure and themselves. Knights and Barons live for pleasure and themselves.

The gatherd storme is rype; the bigge drops falle; The gathered storm is ripe; the huge drops fall;

The forswat meadowes smethe, and drenche the raine; The sunburnt meadows smoke and drink the rain;

The comyng ghastness do the cattle pall, The coming aghastness makes the cattle pale;

And the full flockes are drivynge ore the plaine; And the full flocks are driving o'er the plain;

Dashde from the cloudes the waters flott againe; Dashed from the clouds, the waters float again;

The welkin opes; the yellow levynne flies; The heavens gape; the yellow lightning flies;

And the hot fierie smothe in the wide lowings dies. And the hot fiery steam in the wide flamepot

dies.

Liste! now the thunder’s rattling clymmynge sound Hark! now the thunder's rattling, clamoring sound

Cheves slowlie on, and then embollen clangs, Heaves slowly on, and then enswollen clangs,

Shakes the hie spyre, and losst, dispended, drown’d, Shakes the high spire, and lost, dispended, drown'd,

Still on the gallard eare of terroure hanges; Still

on the coward ear of terror hangs;

The windes are up; the lofty elmen swanges; The winds are up; the lofty elm-tree swings;

Again the levynne and the thunder poures, Again the lightning―then the thunder pours,

And the full cloudes are braste attenes in stonen And the full clouds are burst at once in stormy showers.

showers.

Spurreynge his palfrie oere the watrie plaine, Spurring

his palfrey o'er the watery plain,

The Abbote of Seyncte Godwynes convente came; The Abbot of Saint

Godwin's convent came;

His chapournette was drented with the reine,

His chapournette was drenchèd with the rain,

And his pencte gyrdle met with mickle shame;

And his pinched girdle met with enormous shame;

He aynewarde tolde his bederoll at the same; He

cursing backwards gave his hymns the same;

The storme encreasen, and he drew aside, The storm

increasing, and he drew aside

With the mist almes craver neere to the holme to bide. With the poor

alms-craver, near the holly tree to bide.

His cope was all of Lyncolne clothe so fyne, His cape was

all of Lincoln-cloth so fine,

With a gold button fasten’d neere his chynne; With a gold

button fasten'd near his chin;

His autremete was edged with golden twynne, His ermine robe

was edged with golden twine,

And his shoone pyke a loverds mighte have binne; And

his high-heeled shoes a Baron's might have been;

Full well it shewn he thoughten coste no sinne: Full

well it proved he considered cost no sin;

The trammels of the palfrye pleasde his sighte, The trammels

of the palfrey pleased his sight

For the horse-millanare his head with roses dighte. For

the horse-milliner loved rosy ribbons bright.

“An almes, sir prieste!” the droppynge pilgrim saide, "An alms, Sir

Priest!" the drooping pilgrim said,

“O! let me waite within your covente dore, "Oh, let

me wait within your convent door,

Till the sunne sheneth hie above our heade, Till the

sun shineth high above our head,

And the loude tempeste of the aire is oer; And the loud tempest of the air is o'er;

Helpless and ould am I alas! and poor; Helpless and old am I, alas!, and poor;

No house, ne friend, ne moneie in my pouche; No house, no

friend, no money in my purse;

All yatte I call my owne is this my silver crouche.” All that I call my own is this―my silver cross.

“Varlet,” replyd the Abbatte, “cease your dinne; "Varlet," replied

the Abbott, "cease your din;

This is no season almes and prayers to give; This is no

season alms and prayers to give;

Mie porter never lets a faitour in; My porter never lets a beggar in;

None touch mie rynge who not in honour live.” None touch my

ring who in dishonor live."

And now the sonne with the blacke cloudes did stryve, And now the sun with

the blackened clouds did strive,

And shettynge on the grounde his glairie raie, And

shed upon the ground his glaring ray;

The Abbatte spurrde his steede, and eftsoones roadde The

Abbot spurred his steed, and swiftly rode away.

awaie.

Once moe the skie was blacke, the thunder rolde; Once more the sky

grew black; the thunder rolled;

Faste reyneynge oer the plaine a prieste was seen; Fast running

o'er the plain a priest was seen;

Ne dighte full proude, ne buttoned up in golde; Not full of

pride, not buttoned up in gold;

His cope and jape were graie, and eke were clene; His cape and jape

were gray, and also clean;

A Limitoure he was of order seene;

A Limitour he was, his order serene;

And from the pathwaie side then turned hee, And from the pathway side he turned to see

Where the pore almer laie binethe the holmen tree. Where the poor almer

lay beneath the holly tree.

“An almes, sir priest!” the droppynge pilgrim sayde, "An alms, Sir Priest!" the drooping pilgrim said,

“For sweete Seyncte Marie and your order sake.” "For sweet Saint Mary and your order's sake."

The Limitoure then loosen’d his pouche threade, The Limitour then loosen'd his purse's thread,

And did thereoute a groate of silver take; And from it did a groat of silver take;

The mister pilgrim dyd for halline shake. The

needy pilgrim did for happiness shake.

“Here take this silver, it maie eathe thie care; "Here, take this silver, it may ease thy care;

We are Goddes stewards all, nete of oure owne we "We are God's

stewards all, naught of our own we bear."

bare.

“But ah! unhailie pilgrim, lerne of me, "But ah! unhappy pilgrim, learn of me,

Scathe anie give a rentrolle to their Lorde. Scarce any give a rentroll to their Lord.

Here take my semecope, thou arte bare I see; Here, take my cloak, as thou are bare, I see;

Tis thyne; the Seynctes will give me mie rewarde.” 'Tis thine; the Saints will give me my reward."

He left the pilgrim, and his waie aborde. He left

the pilgrim, went his way abroad.

Virgynne and hallie Seyncte, who sitte yn gloure, Virgin and happy Saints, in glory showered,

Or give the mittee will, or give the gode man power. Let the mighty bend, or the good man be empowered!

TRANSLATOR'S NOTE: It is possible that some words used by Chatterton were his

own coinages; some of them apparently cannot be found in medieval literature. In

a few places I have used similar-sounding words that seem to not overly disturb

the meaning of the poem.― Michael R. Burch

The HyperTexts