The HyperTexts

Finedon’s ‘forgotten’ genius

New book sheds light on ‘wildly unconventional’ son of the lord of the manor

of Finedon whose early death robbed English literature of a great poet

by Simon Edge

originally published by the Northamptonshire Telegraph

On a warm summer’s afternoon in 1867, the young son of a Rutland country

parson was out bathing in a pool of the River Welland near his home. Since he couldn’t swim, he relied on the services of a young student, whom

his father was tutoring for the Oxford entrance exam, to tow him across. They crossed once, but on their return, the student suddenly sank without a

warning. The boy, Walter, managed to turn on his back and keep himself afloat, and

eventually some reapers in the nearby fields heard his cries. But it was too late to help the student. His body was not retrieved for

several hours.

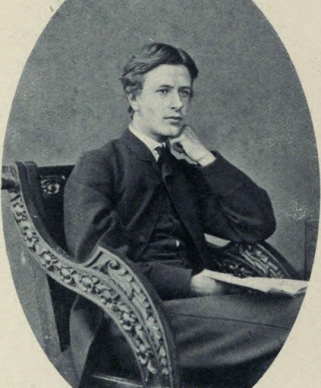

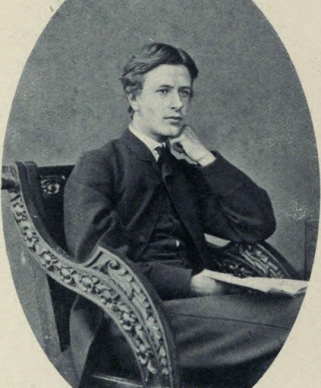

The student’s name was Digby Mackworth Dolben, and his death robbed English

literature

of a boy genius, whose work was said by future poet laureate Robert Bridges to

be equal to “anything that was ever written by any English poet at his age”.

He was also wildly unconventional. The youngest son of the lord of the manor of Finedon, he joined a medieval

religious cult and caused outrage by wandering the country as a barefoot monk.

The poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, subject of my recent novel The Hopkins

Conundrum, was so captivated by a brief meeting that he spent the rest of his

life mourning him.

“He was obviously a highly eccentric person, who was a controversialist at

school and home, and I’m sure he was high maintenance,” says the Rev. Richard

Coles, the broadcaster (and current Strictly Come Dancing contestant) who is also

vicar of Finedon. “But he was very gifted. I’m actually fascinated by him.”

Digby was born in Guernsey in 1848, but the family home was Finedon Hall, a

mansion dating back to Elizabethan times. His father, William Mackworth, had come into the Finedon estate by marrying

Digby’s mother, Frances Dolben, after which he took her surname.

Digby’s father had a contradictory stance on the culture wars raging at the

time between the Oxford Movement, which favoured a revival of Catholic rituals

in the English Church, and ‘Low Church’ Protestants. Digby’s father was fiercely anti-Catholic, but one of the leaders of the

Oxford Movement, Henry Liddon, was briefly curate at Finedon in 1853, and

Digby’s father was also passionately interested in Gothic architecture, which

tended to be the hallmark of a High Church sensibility. He remodelled Finedon Hall to make it look more Gothic, and he built a folly

called the Volta Tower when his eldest son was lost at sea. It was a well-known landmark until it collapsed in 1951, killing the lady who

lived there. “Unfortunately he neglected to use mortar when he built it,” says Coles.

Young Digby was sent to Eton, where he drew attention to himself in various

ways. He had an affair with another boy, which was not itself unusual for an

English public school of that time; but he fell passionately in love and wrote

explicit poetry about it, which was much rarer. Meanwhile he cultivated monkish eccentricities, choosing to singe his hair

with a candle rather than get it cut, and stealing the school’s bread rolls

before breakfast so that other boys could know the joys of fasting.

But it was his open flirtation with Catholicism that got him into real

trouble. He truanted to visit nearby Catholic communities, and joined an eccentric

band of self-styled monks led by a suspect character known as Father Ignatius.

He also genuflected and kept statues of the Virgin Mary. At a time when High Church

‘ritualism’ was seen as such a threat to English

identity that Parliament would shortly pass a law against it, this was beyond

the pale. “It’s hard for us to really begin to understand just how outrageous it was,

for Popish practices to flourish,” says Coles. “It would have been upsetting to Etonian sensibilities. And for Finedonians,

where the Quakers in particular were very strong, to have seen the son of the

hall parading around in a habit must have been very challenging.”

Digby was asked to leave Eton, but he was determined to get to Oxford

University.

He was visiting his cousin Bridges there when he met Hopkins. They spent three

short afternoons together, leaving Hopkins with a lifelong crush on the

magnetic, but not conventionally handsome, Digby.

I dramatise some of that in my novel and I’m pleased to find it is leading to

a rediscovery of Dolben’s work. The American poet Tom Merrill told me after reading The Hopkins Conundrum: “Dolben’s

precocity surprised me – how beyond his years he was. I hope people know about

him. He was a deeply sensitive person, maybe comparable to Shelley.”

In present-day Finedon, the Dolbens are commemorated in the name of a square,

a close, and the Finedon Dolben Cricket Club. Finedon Hall has been divided into luxury flats, where a distant relative of

the Dolbens is among the residents. The immediate family died out with Digby’s

sister Ellen in 1912. Digby, who is buried in the village churchyard, referred to death in a poem

as “sleep, the end of all desire”. His own death seems to have been caused by a stroke – but his insistence on

starving himself may not have helped.

His poems were published by Bridges in 1911, and he still merits an entry in

the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, which says of his work: “As it

stands, it is among the

best of the poetry of the Oxford Movement.” His death a century and a half ago, it adds, “was the end of a life of

exceptional poetic

promise”.

On his anniversary, let’s not forget that life altogether.

NOTE: In Simon Edge's original article as published by the Northamptonshire Telegraph,

Tom Merrill was identified as a Canadian poet. Merrill asked for a correction to

be made, as he is an American poet who now lives in Montreal.

The Hopkins Conundrum by Simon Edge is published by Lightning Books price

£8.99. The book can be purchased

here.

The HyperTexts