The HyperTexts

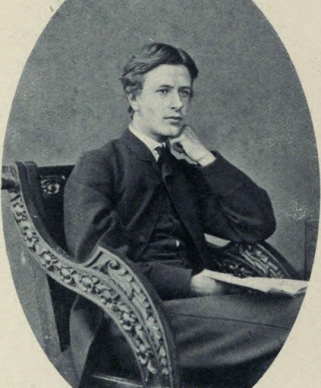

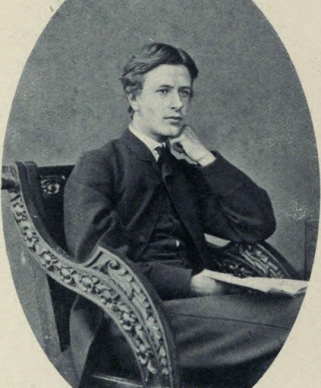

The Best Poems of Digby Mackworth Dolben

On a warm summer afternoon in 1867, Digby Mackworth Dolben drowned at

age nineteen. The poems he left behind were said by future English poet laureate Robert Bridges to

equal "anything that was ever written by any English poet at his age."

According to Simon Edge, author of The Hopkins Conundrum, Gerard Manley Hopkins was "so captivated by a brief meeting [with Dolben] that he spent the rest of his

life mourning him." In a letter to Bridges after

Dolben’s death, Hopkins said "there can very seldom have happened the loss of so

much beauty (in body and mind and life) and of the promise of still more as

there has been in his case." Hopkins also asked Bridges whether Dolben's family

had considered publishing his poems. Fortunately, the independently wealthy

Bridges later published books of poems by both Dolben and Hopkins, or their

poetry might have been lost to the world forever.

Is Dolben merely a literary curiosity today because he attracted the attention

of two famous poets―with possible homoerotic

undertones on Hopkins' part―then died so young

and so tragically? Or does he merit consideration as a poet in his own right?

After his discovery of the prodigy's work thanks to Simon's novel, THT advisory

editor Tom Merrill emailed Simon that "Dolben's precocity surprised me―how

beyond his years he was. I hope people know about him. He was a deeply sensitive

person, maybe comparable to Shelley." Another poet to whom Dolben may be

compared is Thomas Chatterton, the "marvellous boy" who died at age seventeen

and yet was so highly esteemed by Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats and Shelley.

Dolben's poems were published in a single volume by Bridges in 1911;

the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography says that his work stands "among the

best of the poetry of the Oxford Movement." Dolben's death, it adds, "was the end of a life of

exceptional poetic promise." I agree and see no reason that such

exceptional poetry―all the more tantalizing because it was

written at such a young age―should not be read today. Toward that end, here are

the poems of Digby Dolben that strike me as his best, followed by three more

that, according to Bridges, exhibit "complete mastery." The fourth such poem, in

Bridges' opinion, is the first poem below.―Michael R.

Burch, editor, The HyperTexts

There is a Digby Dolben Timeline/Chronology at the bottom of this page,

along with a link to a very interesting Dolben bio written by Simon Edge.

A Song

The world is young today:

Forget the gods are old,

Forget the years of gold

When all the months were May.

A little flower of Love

Is ours, without a root,

Without the end of fruit,

Yet ― take the scent thereof.

There may be hope above,

There may be rest beneath;

We see them not, but Death

Is palpable ― and Love.

Far Above The Shaken Trees

Far above the shaken trees,

In the pale blue palaces,

Laugh the high gods at their ease:

We with tossèd incense woo them,

We with all abasement sue them,

But shall never climb unto them,

Nor see their faces.

Sweet my sister, Queen of Hades,

Where the quiet and the shade is,

Of the cruel deathless ladies

Thou art pitiful alone.

Unto thee I make my moan,

Who the ways of earth hast known

And her green places.

Feed me with thy lotus-flowers,

Lay me in thy sunless bowers,

Whither shall the heavy hours

Never trail their hated feet,

Making bitter all things sweet;

Nevermore shall creep to meet

The perished dead.

There 'mid shades innumerable,

There in meads of asphodel,

Sleeping ever, sleeping well,

They who toiled and who aspired,

They, the lovely and desired,

With the nations of the tired

Have made their bed.

There is neither fast nor feast,

None is greatest, none is least;

Times and orders all have ceased.

There the bay-leaf is not seen;

Clean is foul and foul is clean;

Shame and glory, these have been

But shall not be.

When we pass away in fire,

What is found beyond the pyre?

Sleep, the end of all desire.

Lo, for this the heroes fought;

This the gem the merchant bought,

This the seal of laboured thought

And subtilty.

Beyond

Beyond the calumny and wrong,

Beyond the clamour and the throng,

Beyond the praise and triumph-song

He passed.

Beyond the scandal and the doubt,

The fear within, the fight without,

The turmoil and the battle-shout

He sleeps.

The world for him was not so sweet

That he should grieve to stay his feet

Where youth and manhood's highways meet,

And die.

For every child a mother's breast,

For every bird a guarded nest;

For him alone was found no rest

But this.

Beneath the flight of happy hours,

Beneath the withering of the flowers

In folds of peace more sure than ours

He lies.

A night no glaring dawn shall break,

A sleep no cruel voice shall wake,

An heritage that none can take

Are his.

From Martial

In vain you count his virtues up,

His soberness commend;

I like a steady servant,

But not a steady friend.

Poppies

Lilies, lilies not for me,

Flowers of the pure and saintly―

I have seen in holy places

Where the incense rises faintly,

And the priest the chalice raises,

Lilies in the altar vases,

Not for me.

Leave untouched each garden tree,

Kings and queens of flower-land.

When the summer evening closes,

Lovers may-be hand in hand

There will seek for crimson roses,

There will bind their wreaths and posies

Merrily.

From the corn-fields where we met

Pluck me poppies white and red;

Bind them round my weary brain,

Strew them on my narrow bed,

Numbing all the ache and pain.―

I shall sleep nor wake again,

But forget.

Enough

When all my words were said,

When all my songs were sung,

I thought to pass among

The unforgotten dead,

A Queen of ruth to reign

With her, who gathereth tears

From all the lands and years,

The Lesbian maid of pain;

That lovers, when they wove

The double myrtle-wreath,

Should sigh with mingled breath

Beneath the wings of Love:

'How piteous were her wrongs,

Her words were falling dew,

All pleasant verse she knew,

But not the Song of songs.'

Yet now, O Love, that you

Have kissed my forehead, I

Have sung indeed, can die,

And be forgotten too.

There Was One Who Walked In Shadow

There was one who walked in shadow,

There was one who walked in light:

But once their way together lay,

Where sun and shade unite,

In the meadow of the lotus,

In the meadow of the rose,

Where fair with youth and clear with truth

The Living River flows.

Scarcely summer stillness breaking,

Questions, answers, soft and low—

The words they said, the vows they made,

None but the willows know.

Both have passed away for ever

From the meadow and the stream;

Past their waking, past their breaking

The sweetness of that dream.

One along the dusty highway

Toiling counts the weary hours,

And one among its shining throng

The world has crowned with flowers.

Sometimes perhaps amid the gardens,

Where the noble have their part,

Though noon's o'erhead, a dew-drop's shed

Into a lily's heart.

This I know, till one heart reaches

Labour's sum, the restful grave,

Will still be seen the willow-green,

And heard the rippling wave.

A Sea Song

In the days before the high tide

Swept away the towers of sand

Built with so much care and labour

By the children of the land,

Pale, upon the pallid beaches,

Thirsting, on the thirsty sands,

Ever cried I to the Distance,

Ever seaward spread my hands.

See, they come, they come, the ripples,

Singing, singing fast and low,

Meet the longing of the sea-shores,

Clasp them, kiss them once, and go.

'Stay, sweet Ocean, satisfying

All desires into rest—'

Not a word the Ocean answered,

Rolling sunward down the west.

Then I wept: 'Oh, who will give me

To behold the stable sea,

On whose tideless shores for ever

Sounds of many waters be?'

Methought, Through Many Years And Lands

Methought, through many years and lands,

I sped along an arrowy flood,

That leapt and lapt my face and hands,

I knew not were it fire or blood.

I saw no sun in any place;

A ghastly glow about me spread,

Unlike the light of nights and days,

From out the depth where writhe the dead.

I passed―their fleshless arms uprose

To draw me to the depths beneath:

My eyes forgot the power to close,

As other men's, in sleep or death.

I saw the end of every sin;

I weighed the profit and the cost;

I felt Eternity begin,

And all the ages of the lost.

The Crucifix was on my breast;

I pressed the nails against my side;

And unto Him, Who knew no rest

For thirty years, I turned and cried:

'Sweet Lord! I say not, give me ease;

Do what Thou wilt, Thou doest good;

And all Thy saints went up to peace,

In crowns of fire or robes of blood.'

We hurry on, nor passing note

We hurry on, nor passing note

The rounded hedges white with May;

For golden clouds before us float

To lead our dazzled sight astray.

We say, 'they shall indeed be sweet

'The summer days that are to be'—

The ages murmur at our feet

The everlasting mystery.

We seek for Love to make our own,

But clasp him not for all our care

Of outspread arms; we gain alone

The flicker of his yellow hair

Caught now and then through glancing vine,

How rare, how fair, we dare not tell;

We know those sunny locks entwine

With ruddy-fruited asphodel.

A little life, a little love,

Young men rejoicing in their youth,

A doubtful twilight from above,

A glimpse of Beauty and of Truth,—

And then, no doubt, spring-loveliness

Expressed in hawthorns white and red,

The sprouting of the meadow grass,

But churchyard weeds about our head.

Homo Factus Est

Come to me, Belovèd,

Babe of Bethlehem;

Lay aside Thy Sceptre

And Thy Diadem.

Come to me, Belovèd;

Light and healing bring;

Hide my sin and sorrow

Underneath Thy wing.

Bid all fear and doubting

From my soul depart,

As I feel the beating

Of Thy Human Heart.

Look upon me sweetly

With Thy Human Eyes

With Thy Human Finger

Point me to the skies.

Safe from earthly scandal

My poor spirit hide

In the utter stillness

Of Thy wounded Side.

Guide me, ever guide me,

With Thy piercèd Hand,

Till I reach the borders

Of the pleasant land.

Then, my own Belovèd,

Take me home to rest;

Whisper words of comfort;

Lay me on Thy Breast.

Show me not the Glory

Round about Thy Throne;

Show me not the flashes

Of Thy jewelled Crown.

Hide me from the pity

Of the Angels' Band,

Who ever sing Thy praises,

And before Thee stand.

Hide me from the glances

Of the Seraphin,―

They, so pure and spotless,

I, so stained with sin.

Hide me from St. Michael

With his flaming sword:―

Thou can'st understand me,

O my Human Lord!

Jesu, my Belovèd,

Come to me alone;

In Thy sweet embraces

Make me all Thine own.

By the quiet waters,

Sweetest Jesu, lead;

'Mid the virgin lilies,

Purest Jesu, feed.

Only Thee, Belovèd,

Only Thee, I seek.

Thou, the Man Christ Jesus,

Strength in flesh made weak.

Sister Death

My sister Death! I pray thee come to me

Of thy sweet charity,

And be my nurse but for a little while;

I will indeed lie still,

And not detain thee long, when once is spread,

Beneath the yew, my bed:

I will not ask for lillies or for roses;

But when the evening closes,

Just take from any brook a single knot

Of pale Forget-me-not,

And lay them in my hand, until I wake,

For his dear sake;

(For should he ever pass and by me stand,

He might understand―)

Then heal the passion and the fever

With one cool kiss, for ever.

NOTE: The poems above are, in my personal opinion, the best poems by Digby

Dolben. The poems below were named by Robert Bridges as the most masterful of

Dolben's poems. The only poem on which we agreed was "A Song," the first poem on

this page. ― Michael R. Burch

From Sappho

Thou liest dead,―lie on: of thee

No sweet remembrances shall be,

Who never plucked Pierian rose,

Who never chanced on Anterôs.

Unknown, unnoticed, there below

Through Aides' houses shalt thou go

Alone,―for never a flitting ghost

Shall find in thee a lover lost.

The Shrine

There is a shrine whose golden gate

Was opened by the Hand of God;

It stands serene, inviolate,

Though millions have its pavement trod;

As fresh, as when the first sunrise

Awoke the lark in Paradise.

'Tis compassed with the dust and toil

Of common days, yet should there fall

A single speck, a single soil

Upon the whiteness of its wall,

The angels' tears in tender rain

Would make the temple theirs again.

Without, the world is tired and old,

But, once within the enchanted door,

The mists of time are backward rolled,

And creeds and ages are no more;

But all the human-hearted meet

In one communion vast and sweet.

I enter―all is simply fair,

Nor incense-clouds, nor carven throne

But in the fragrant morning air

A gentle lady sits alone;

My mother―ah! whom should I see

Within, save ever only thee?

He Would Have His Lady Sing

Sing me the men ere this

Who, to the gate that is

A cloven pearl uprapt,

The big white bars between

With dying eyes have seen

The sea of jasper, lapt

About with crystal sheen;

And all the far pleasance

Where linkèd Angels dance,

With scarlet wings that fall

Magnifical, or spread

Most sweetly over-head,

In fashion musical,

Of cadenced lutes instead.

Sing me the town they saw

Withouten fleck or flaw,

Aflame, more fine than glass

Of fair Abbayes the boast,

More glad than wax of cost

Doth make at Candlemas

The Lifting of the Host:

Where many Knights and Dames,

With new and wondrous names,

One great Laudaté Psalm

Go singing down the street;―

'Tis peace upon their feet,

In hand 'tis pilgrim palm

Of Goddes Land so sweet:―

Where Mother Mary walks

In silver lily stalks,

Star-tirèd, moon-bedight;

Where Cecily is seen,

With Dorothy in green,

And Magdalen all white,

The maidens of the Queen.

Sing on―the Steps untrod,

The Temple that is God,

Where incense doth ascend,

Where mount the cries and tears

Of all the dolorous years,

With moan that ladies send

Of durance and sore fears:―

And Him who sitteth there,

The Christ of purple hair,

And great eyes deep with ruth,

Who is of all things fair

That shall be, or that were,

The sum, and very truth.

Then add a little prayer,

That since all these be so,

Our Liege, who doth us know,

Would fend from Sathanas,

And bring us, of His grace,

To that His joyous place:

So we the Doom may pass,

And see Him in the Face.

For a brief bio of Digby Dolben by Simon Edge, please click here:

Digby Dolben Bio.

Digby Dolben Chronology/Timeline

1772: According to Louisa May Portman, the niece of George Digby Wingfield

Digby, their ancestor Elizabeth Digby, later Lady Dolben, was an "especial

favourite" of the poet Alexander Pope.

1848: Digby Augustus Stewart Mackworth Dolben is born on

February 8, 1848 on the English Channel island of Guernsey. His father, William Harcourt Isham

Mackworth (1806-1872), a younger son of Sir Digby Mackworth, the 3rd Baronet,

takes the additional surname Dolben after he marries Frances, the heiress of Sir

John English Dolben, the 4th Baronet.

1853: While the young Digby Dolben is growing up in the Finedon parish of

Northamptonshire, Gerard Manley Hopkins' future spiritual mentor, Henry Parry

Liddon, is briefly in charge of the parish. Dolben attends Cheam School, whose

alumni include Prince Philip, Prince Charles and Randolph Churchill (the father

of Winston Churchill).

1862: Digby Dolben enters Eton College around age fourteen, where he studies

under the influential Master William Johnson Cory, whose collection of verses

Ionica would influence his own poetry. At Eton, Dolben's distant cousin Robert

Bridges is his senior and takes him under his wing. According to Bridges, his

cousin was tall and pale, with delicate features and an "abstracted manner" that

made him seem like a "different species" from the other students.

Furthermore, he had "a

spirit of mischief as wanton as Shelley's." The rugged Bridges and the delicate

Dolben were very different animals, but they shared passions for poetry and

religion (Bridges called them both "high church boys").

1863: Dolben causes considerable scandal at Eton with his eccentric,

exhibitionist behavior. He writes love poems to another pupil, Martin Le Marchant

Gosselin, whom Bridges later dubs "Archie" to keep his identity secret.

Dolben also

defies his strict Protestant upbringing by joining a High Church Puseyite group

of pupils. He claims allegiance to the Order of St. Benedict, affects a

monk's habit, traipses around barefoot, and employs the signature "Dominic." He also considers a

conversion to Roman Catholicism, which his family considers beyond the pale. Around this time Dolben destroys

all his poems by burning them, in what Bridges calls a "holocaust." (The love

poems to "Archie" are posited by Bridges as a reason for the holocaust, but

then why

were all the other poems destroyed?) Bridges leaves Eton for Oxford in July 1863. On

July 30, Dolben is dismissed from Eton for a period of time, after engaging in a

secret meeting with Jesuits. Bridges and Dolben begin to correspond by letter on

August 1. (Bridges would publish a number of these letters in 1911,

providing us with a good bit of historical information about Dolben.) In late

1863 there was no sign of any Dolben poems being written since the holocaust,

according to Bridges.

1864: In early 1864, Dolben is fasting and stealing

the breakfast rolls of other students, apparently to introduce them to the joys

of fasting! According to Bridges, Dolben resumes writing poetry around Lent.

(This means all Dolben's published poems were written in less than three

years.) Dolben announces that he is now Brother Dominic. He is writing religious

poetry and expressing hopes of entering Oxford, but alas his Greek is not up to

snuff and he is constantly in search of tutors. "Homo Factus Est" may be Dolben's

first mature poem. According to Bridges, William Cory crows that the poem is "better

than Newman" (i.e., the celebrated Cardinal John Henry Newman, a leading figure

of the Oxford Movement). Six of Dolben's poems are published in the Union

Review. Not bad for a sixteen-year-old!

1865: On his seventeenth birthday, Dolben is introduced by Bridges, now an

undergraduate at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, to Gerard Manley Hopkins, a

student at Balliol. According to Hopkins biographer Norman White, this encounter

greatly perturbs Hopkins. Another biographer, Robert Bernard Martin, asserts

that Hopkins' meeting with Dolben is "quite

simply, the most momentous emotional event of [his] undergraduate years,

probably of his entire life". Hopkins is apparently smitten with Dolben and

his diary details his "suppressed erotic

thoughts" about the younger poet. Hopkins keeps up a correspondence with Dolben and composes two poems about

him: "Where art thou friend" and

"The Beginning of the End." Hopkins' High Anglican confessor seems to have

forbidden him to have any contact with Dolben except by letter. According to

Bridges, the quality of Dolben's poems begins to "mature" in 1865 as he turns

increasingly from Christianity to a Greek or "pagan" idea of beauty.

1866: By this time, now living at Boughrood and studying under Henry de Winton

for the Oxford entrance exams, Doblen is writing poems of "rarest attainment,"

according to Bridges.

1867: Dolben faints during his Oxford entrance exams on May 2, 1867 and fails. On June 15 he travels to meet a new tutor. Thirteen days later,

Dolben drowns in the River Welland (actually, a sluggish brook) on June 28, 1867

while bathing with the ten-year-old son of his new tutor, C. E. Prichard, Rector

of South Luffenham. Dolben is only nineteen at the time. Did he have another

fainting spell? Did he commit suicide, out of despair? Was it a tragic accident?

A possible clue: Prichard wrote that Dolben was very pale and "might have

looked in ill health." After his death, W. B. Gamlen, Secretary of the Oxford

University Chest, recollected Dolben's "distinguished appearance, and the dreamy

far-away look in his eyes." Gamlen concluded that at Luffenham he had been in

"constant contact" with a "highly-cultivated intelligence" beyond his ability to

appraise.

1911: Robert Bridges, poet laureate from 1913 to 1930, edits and publishes a

book

of Dolben's verse, Poems.

1932: Bridges includes Dolben in Three Friends: Memoirs of Digby Mackworth

Dolben, Richard Watson Dixon, Henry Bradley.

1981: The Poems and Letters of Digby Mackworth Dolben 1848–1867 is

published.

2017: Hopkins' infatuation for Dolben and Dolben's poetry and tragic death feature in Simon

Edge's novel The Hopkins Conundrum.

The HyperTexts