The HyperTexts

Makoto Fujimura

Makoto Fujimura is an artist, writer and speaker. His visual art has been

exhibited at galleries and museums around the globe. A popular speaker, he has

lectured at numerous conferences, universities and museums, including the Aspen

Institute, Yale and Princeton Universities, Sato Museum and the Phoenix Art

Museum. Fujimura founded the International Arts Movement in 1992.

Golden Summer

White Tree 2000

"We now begin to realize what we do is only temporary and indefinable.

Incomplete gestures must be made, because reality beckons us to respond. Beauty,

however peripheral, insists that we remain faithful to who we are, as we

are."—Makoto Fujimura, "Gravity and Grace"

Makoto Fujimura's work combines traditional Japanese painting technique with a Western

approach to abstraction. Born in Boston in 1960, Fujimura earned his B.A. at

Bucknell, then went on to receive his Master of Fine Arts and Doctorate degrees from the Tokyo National

University of Fine Arts and Music, where he studied the Japanese traditional technique of

Nihonga. This technique uses ground minerals such as azurite, malachite and

cinnabar mixed with animal hide glue applied to handmade paper. Western

artists who have influenced his work include Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock. In

1990, he founded The International

Arts Movement. In 1992 Fujimura was the youngest artist ever to have had a

piece acquired by Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo.

More recently, Fujimura's work has been showcased at the Bellas Artes Gallery in

Santa Fe, NM; at the Dillon Gallery in Oyster Bay, NY; as well as at

Kristen Frederickson Contemporary Art in New York City. Public collections

include the Saint Louis Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo and the

Time Warner/AOL/CNN building in Hong Kong. He was appointed to the National

Council on the Arts, a six year Presidential appointment, in 2003.

"The idea of forging a new kind of art, about hope, healing,

redemption, refuge, while maintaining visual sophistication and intellectual

integrity is a growing movement, one which finds Fujimura's work at the

vanguard." -- Noted artist and critic Robert Kushner

Between Two Waves of the Sea

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea.

Quick now, here, now, always—

A condition of complete simplicity

T.S. Eliot, Little Gidding, The Four Quartets

Kristen Frederickson, in an essay written for a 2004 exhibit, wrote: "The exhibition of new paintings by Makoto Fujimura is inspired

and informed by T.S. Eliot's last poem, 'Four Quartets.' While

'The Wasteland' is considered by many to be the greatest poem of the

twentieth century, for Fujimura 'Four Quartets' achieves an even clearer

focus on the fundamental questions of art and literature, among them

sacrifice, mystery, intuitive response and the eloquence of

materiality... There is a component of these paintings that cannot be seen except by

the naked eye: photographic representation is an inadequate translation,

perhaps more for these works than most art. As the eye travels

from one moment of the painting to another - from a glistening river of

blue to teardrops of green, streaks of vermilion to a shimmering layer

of gold leaf falling perilously across the surface - there is an element

of utter abstraction and peace that belies the intense training and

experience required to produce these paintings."

Complete text and other "Four Quartets" paintings available:

Please contact Kristen Frederickson Contemporary Art at 149 Reade St,

NYC 10013 212.566.7787 for inquiries regarding "Four

Quartets" paintings.

Beauty Without Regret

By Makoto Fujimura

The layers of azurite pigments, spread

over paper as I let the granular pigments cascade. My eyes see much more than

what my mind can organize. As the light becomes trapped within pigments, a

"grace arena" is created, as the light is broken, and trapped in

refraction. Yet, my gestures are limited, contained, and gravity pulls the

pigments like a kind friend.

Every beauty suffers. A research scientist friend once told me that the

autumn leaves are most beautiful on the trees by the roadside because they

happen to be distressed by the salt and pollution. Every sunset is a reminder of

the impending death of Nature herself. The minerals I use must be pulverized to

bring out their beauty. The Japanese were right in associating beauty with

death.

Art cannot be divorced from faith, for to do so is to literally close our

eyes to that beauty of the dying sun setting all around us. Every beauty also

suffers. Death spreads all over our lives and therefore faith must be given to

see through the darkness, to see through the beauty of "the valley of the

shadow of death".

Prayers are given, too, in the layers of broken, pulverized pigments. Beauty is

in the brokenness, not in what we can conceive as the perfections, not in the

"finished" images but in the incomplete gestures. Now, I await for my

paintings to reveal themselves. Perhaps I will find myself rising through the

ashes, through the beauty of such broken limitations.

Copyright Makoto Fujimura. Used by permission.

Columbine Flowers

By Makoto Fujimura

June 2001

In the aftermath of the Columbine High school shooting, and upon a recommendation by a photographer friend (who covered

the tragic event for the New York Post), I walked in the mountains of Colorado,

looking for wild columbine flowers. They grow numerous on the sunny mountain

faces in summer, white flowers with purple petals and tails like tentacles.

I noticed that there were a few flowers growing in the shade of trees.

Instead of purple petals, they were completely white, almost transparent. The

delicate flowers symbolized for me perfectly the fragility of lives, so young,

haunted by the encroaching darkness of violence. The beauty of them so reminded

me of one girl who was reported to have looked in the eyes of the perpetrator

who held a gun to her head, taunting her, "Do you still believe in

God?" She said "Yes, I believe" and was shot.

Later another friend told me that the columbines were the early church's

symbol for the Holy Spirit. When I paint the columbines, they come out almost

like angels.

Copyright Makoto Fujimura. Used by permission.

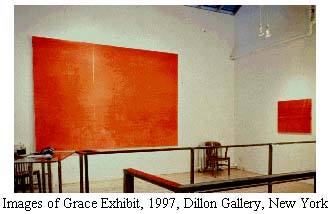

Images of Grace

By Makoto Fujimura

Lecture, September 17-18, 1997

Thank you for coming to this exhibit, Images of Grace. I want to start out by

thanking the people who work here and those who helped out. There are many of

you in the audience who are my images of grace more than my works. The public

sees the artistic accomplishment as an individual accomplishment, and yet I

know, as an artist, that without the "behind-the-scene" support, I

cannot accomplish much at all. Thank you.

We had more than four hundred people come to the opening of this exhibition and

I only had time to spend with maybe thirty people. Many have come up to

me--total strangers, both here and in Japan--and they ask me deep questions

about life, about spiritual issues. They open their lives to me and I find it

very gratifying in one sense but also frustrating because I cannot deal with

every question as much as I would like to. So, the impetus behind tonight is to

try to address some of those points in detail.

I just received a fax from a museum curator in Japan. I had sent him a box of

catalogs from this show. He asked me, "What does grace mean? Can you

explain it to me so I can relay your thoughts to other curators?" I have to

fax back to him and tell him that there is not really an appropriate Japanese

word for it. There are words similar to grace, but nothing that conveys its full

meaning. Then when I thought about the word "grace" in English, I

realized that we do not fully understand the word either. Often this word seems

"Hallmark" sweet. I have, in the past two years as I prepared for this

show, delved deeper into the meaning of this word and found the word to be both

practical and complex. Such a search allows us to ask some of the most important

questions in life. An artist strives to get at the essence of things; whether

they be trees, experiences, flowers or landscapes. The more one understands what

this word has to offer in its depth, its reality, the more one realizes how much

we do not understand or grasp. You can only get at an infinitesimal portion of

this great reality. I have tasted this bittersweet reality of what grace means.

This is a heavenly word; it forces us to seek the transcendent, but at the same

time this word affirms earthly reality as it is, sometimes grim, sometimes

glorious.

Even the materials and technique I use reflect both the transcendent and the

immanent. As many of you know I spent six and a half years in Japan studying the

technique of Nihonga, which is literally translated as "Japanese style

painting." I use materials and techniques developed over one thousand years

of Japanese paintings but using the visual vocabulary of twentieth century,

contemporary art. I import the materials from Japan--the works are all done on

paper--thin, hand-made paper. Some of them are stretched over canvases, some of

them over panels. For pigments I use mineral pigments, actually semi-precious

stone crushed, such as azurite, malachite, cinnabar pigments. These pigments,

when finely ground, become a lighter shade of color. Coarsely ground, they

remain dark and intense as on the left side of "Sacrificial Grace."

You can see on "Grace Foretold," the blue that is flowing from the

top--that is the azurite pigment.

Even the materials and technique I use reflect both the transcendent and the

immanent. As many of you know I spent six and a half years in Japan studying the

technique of Nihonga, which is literally translated as "Japanese style

painting." I use materials and techniques developed over one thousand years

of Japanese paintings but using the visual vocabulary of twentieth century,

contemporary art. I import the materials from Japan--the works are all done on

paper--thin, hand-made paper. Some of them are stretched over canvases, some of

them over panels. For pigments I use mineral pigments, actually semi-precious

stone crushed, such as azurite, malachite, cinnabar pigments. These pigments,

when finely ground, become a lighter shade of color. Coarsely ground, they

remain dark and intense as on the left side of "Sacrificial Grace."

You can see on "Grace Foretold," the blue that is flowing from the

top--that is the azurite pigment.

I use them not just because they are beautiful, which they are, but because they

have this wonderful lineage. I use them because of the specific symbolism

attached to them. For me, mineral pigments have significance as symbols; they

symbolize God's spiritual gifts to people and the glories of the saints in the

Bible. In Solomon's temple these precious stones were embedded in the walls as

well as in the garments of the high priest. When you look closely at these

paintings you see that they have a peculiar surface--they glitter and shine.

Crushed minerals, therefore, symbolize gifts both from heaven and earth, and

point to my deeper struggle to return the gifts given to the Creator.

I use them not just because they are beautiful, which they are, but because they

have this wonderful lineage. I use them because of the specific symbolism

attached to them. For me, mineral pigments have significance as symbols; they

symbolize God's spiritual gifts to people and the glories of the saints in the

Bible. In Solomon's temple these precious stones were embedded in the walls as

well as in the garments of the high priest. When you look closely at these

paintings you see that they have a peculiar surface--they glitter and shine.

Crushed minerals, therefore, symbolize gifts both from heaven and earth, and

point to my deeper struggle to return the gifts given to the Creator.

Gold has always been a symbol of divinity because it does not change. I have

used the image of cascading gold as a metaphor--it speaks of the City of God

descending among the cities of men. Silver, on the other hand, does change and

oxidize, tarnishing over time, so it is a symbol of death within. In Japan,

silver has always symbolized death but also the fleeting reality of our

existence; in Japanese culture death is seen as something that needs to be

viewed as something beautiful. These materials and the technique itself capture

the essence of an aesthetic-world view developed over centuries of Japanese art.

At the same time, I believe the range of expression and surface-presence of

these materials makes them appropriate contemporary medium, a visual diction

that bridges the past and the present.

Grace Foretold and River Grace (Red) came about based on my experience of

traveling with my family to Niagara. The splendor and majesty and power of the

falls--no matter how much they commercialize it--impress and awe us still. I

wanted to, afterwards, go to a place called Lewistown, which is five miles down

stream from Niagara Falls. Geologists tell us that these magnificent falls began

at Lewistown some thousands of years ago. I went there and it is simply a river

now, flowing very deep. What an amazing thing to be standing in front of this

river and to think that thousands of years ago something happened here. I do not

know if it was a geological shift, a glitch in the rocks, temperature changing,

or what, but something caused this river to become the falls. The following I

wrote soon afterwards to try to capture what I experienced there fishing with my

sons, Ty, eight, and C.J., five.

"Each year, the falls recedes a few inches as the water wears down the

rocks. We walked the edge of the pier, along with few other fishermen. I put a

delicate, small crayfish on C.J.'s hook and waited. In a moment, his line swam

against the current. I took the rod, set the hook, and returned the rod to

C.J.'s hands; but in the process realized we had quite a fish. We fought it for

a while and asked a local fisherman to help us land it. He, chewing on a now-dying ember of a cigarette, skillfully turned the net, swooped the 21 inch

bronzeback, a smallmouth bass. C.J., upon examining the fish, took a few steps

back. It was as long as his legs. The fish swayed its tail in slow motion, and I

felt, with my thumbs as I lifted the fish, its abrasive teeth. The red gills

moved in and out; the hook had set too deeply as the fish swallowed the soft crayfish

whole. We decided to give the fish to the fisherman. The old man took the fish

without a word, grasped its mouth with his tanned, skinny hands full of veins,

locked the chain stringer in its mouth and gills and lowered the fish, along

with a few other bronzebacks, into the water.

In the dying light, I pondered the contour of C.J. 's back, who sat ever more

attentively to the river, the line, his rod. More bass swam in this river, many

many more. Those bronzebacks would swim deep, reflecting the sun handsomely in

the translucent, malachite river flowing in front of us so deep and powerful. I

looked over to the mist of the falls; a storm was approaching, perhaps over the

falls now. Then, I saw in my mind's eye what would later become a painting.

I recognized something. The scene came from an earlier work in which the field

was red. I saw the malachite river not malachite but red, a deep, cinnabar red.

Then, in an instant, it was back to malachite, perhaps even clearer than it was

before. What did I see? I was not sure. I do not think it was a

"vision" but a recognition. I saw the scene with the artist's eye,

with a visual language I had been developing. In one sense, my paintings that I

had painted earlier paved the way for this experience.

I had always used red (shu) pigments as symbol of atonement and redemption. Shu

pigments (vermilion) painted with Nihonga method on paper possess unusual

quality of lightness and depth. Red painted with acrylic or oil does not have

the warmth nor the light that Japanese vermilion does. These reds, combined with

coarse, cinnabar pigments, create a unique illusion of space within the

semi-opaque layers of pigments. Rothko and Newman both understood the power of

red. I wanted to create work that had both the ethereal space of Rothko, but the

directness and power of a Newman.

I initially thought to contrast the horizon line with a gestural vertical motion

by using a wing motif. But I thought of Newman's architectural paintings and

came up with a unique idea. I remembered, in one of my dealings with classical

paintings, that pure gold line, thinly painted, can dominate a very large space.

I like gold lines, as it alludes Blake's words:

I give you the end of a golden string,

Only wind it into a ball,

It will lead you in at Heaven's gate

Built in Jerusalem's wall.

Jerusalem (plate 77, p. 716)

A vision of death accompanies a vision of life; every parent must experience the

fear of losing a child. Despite the communion and closeness I felt to my son, at

the same time, I felt so alone and naked, alienated from the very experience in

which I found such intimacy. A moment flees you before you desire, and the

struggle is trying to fight your inclination to grab hold and strangle and kill

the very life before it escapes. Every experience is both eternal and fleeting

at the same time, every relationship depends on trusting through change and

growth. Eternity grasped means, in our finiteness, frustration of seeing that

moment escape through our fingers. Like the bronzeback, the beauty of the

substance never remains. We cannot grasp the moment, but we can only let go.

Because this moment will be gone; and C.J. would grow, I would change, the

Niagara Falls will move another few meters back to the mountains.

Art mirrors this struggle and captures the process of letting go. Every stroke

pushes the painting to sacrifice itself: every creative act destroys something

previously built. Imagination reveals not new vistas but revelations of reality

behind reality. All art points to a transaction between reality of the seen and

reality of the unseen. Art reaches out to the extra-dimensionality of God and

God's Kingdom Reality. Art uses frail, earthly materials, its limited

dimensionality, to open ourselves to the experience of the Heavenly realm.

Grace comes to us both hidden and revealed. Like the golden line here in River

Grace (Red), it remains peripheral to us, often unnoticed. It may signify the

inconsequential, a small beginning of something new. We certainly do not

recognize grace enough in our lives. This gift of grace is like the air we

breathe or the light we see or the water we drink. Unless it's removed from us

we do not appreciate it enough. But when you do see grace, just like this golden

line, it dominates everything you see and it becomes a significant indispensable

part of the whole.

Grace comes to us both hidden and revealed. Like the golden line here in River

Grace (Red), it remains peripheral to us, often unnoticed. It may signify the

inconsequential, a small beginning of something new. We certainly do not

recognize grace enough in our lives. This gift of grace is like the air we

breathe or the light we see or the water we drink. Unless it's removed from us

we do not appreciate it enough. But when you do see grace, just like this golden

line, it dominates everything you see and it becomes a significant indispensable

part of the whole.

On the other hand, grace is like this cascading gold here on Grace Foretold.

Like the Niagara Falls, a costly city of God may overwhelm us, and such vision

captures us both inescapably and irreversibly.

A friend of mine, when he learned that I was embarking on this series of grace, said, "You've got to see Les Miz." He treated my wife and me and we

went to see the Broadway play Les Miserable. Like Jean Val Jean, some are

forever changed by that one significant moment, as when the priest forgave him

for stealing his spoons. The priest tells him that he did not steal, that it was

given to him, and presents him the silver candlesticks along with the spoons.

When you see the musical, you see that he always carries the candlesticks with

him, everywhere he goes, as a reminder of this redemptive grace. He ends up even

sacrificing his own life for the freedom of being forgiven.

Ryunoske Akutagawa, a postwar Japanese writer, one of the most influential

writers of postwar Japan, wrote a short story called "A Silver Thread of a

Spider," a story of man like Jean Val Jean. A man "who committed many

crimes, such as arson and murder--and yet on one occasion he found kindness in

his heart for a spider." While taking a walk one day, he saw a spider and

instead of crushing it with his foot, he decided to spare its life. Therefore,

when he got to purgatory, Buddha lowered him the silver thread of a spider as

his last chance for salvation. He grabbed hold of the thread and climbed up it;

but halfway up he made a mistake. He looked down and saw all these people

climbing up the thread after him. Millions of people. And, as soon as he thought

in his heart--even before it came out of his mouth--when he yelled, "get

off this thread, this is mine, my thread," the spider web broke above him.

I was thinking about that story when I painted River Grace--Red. So much of my

experience here on this earth points to this man's experience. Our hearts

desperately try to find that thread that would take us into another level of

experience. We can all fill in the blank here--if only we had _____ . Perhaps it is things hoped for in a career,

relationships, health, children--I do not know what they are, but we all have

them. The problem is that once we have it, we are afraid to share it, afraid

that the thread that we are holding onto will break.

My struggle in using these gorgeous materials--they are really gifts from

God--is that the more that I thought about the beauty behind these materials,

the power of them, the glory behind the beauty started to crush my heart. A

schism developed inside my heart. The more I succeeded in expression, the less

success I was finding in my own heart and in my relationships with my wife and

with friends. It was tormenting because I thought of myself as a

"righteous" man who wanted to be a good husband, who wanted to be a

good person. Yet, it felt as if one had to choose between important

relationships, or investing one's time as an artist in one's craft, exploring

this trans-dimensional area which brings so much satisfaction and glory. The

more you find glory in your works, somehow, the less you are able to see that

glory in your own life. Art then was my treasure, it was my holy work, and it

was my identity.

There is a man in the Bible who coined this word "grace." His name was

Saul, later Paul, a first century orthodox Jew. My treasure was my art, his was

his lineage. He had everything given to him, "a Hebrew of Hebrews," he

would boast. He had, as orthodox Jew, an unwavering allegiance to the Torah,

God's law. He was so much like this man climbing up the spider web. He tried to

fulfill his life by following what he thought God was asking him to do, to be

"faultless" in his zeal to obey not only God's law but the human-made laws

of his religion. Saul was determined to persecute the early church--people who

called themselves The Way--because these people had seen the Messiah resurrected.

The Messiah claimed to be the "way, truth and life," thus claiming

exclusivity to the path to God. For Saul, this was a tremendous insult against

his own path of obedience to the Law. He was willing to do anything to sacrifice

his time and his life to destroy this fast-growing movement.

Something happened on the way to Damascus. He came face to face with this

resurrected Messiah, the one that he thought did not exist, or was unwilling to

admit that he existed. He met him person to person and what used to be a

religion turned into something else, turned into a relationship between the

Maker and a creature. Later on, Paul looked back to this experience and he was

trying to find a word that would best describe what had happened to him. He

could not find an appropriate word in Greek to fully capture this extraordinary

experience. He had to describe the indescribable, a cosmic gift to a most

unlikely recipient. He, being a good communicator, invented a word. He used the

word for gift (charisma) in Greek and shortened it into the word for grace

(charis). Grace to him was a gift.

Later, Paul repeats his poetic language to describe his experience at Damascus.

He writes in the letter to the Ephesians, "For it is by grace you have been

saved, through faith--and this not from yourselves, it is the gift of God--not

by works, so that no one can boast." He goes on to say, "For we are

God's workmanship, created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God has

prepared in advance for us to do." "Workmanship" in Greek is

"poiema" from which we get the word "poem." Notice the

curious contradiction there; Paul starts out saying that everything is by grace,

grace is a gift, 100% God's gift and then he turns around and says, "For

you are God's workmanship," we are God's artworks. But it is only by God's

grace that we can become God's artworks.

Paul's experience must have been like the (see "Grace Foretold")

cascading gold of grace. For some, the experience of grace comes very slowly,

imperceptibly, like the golden line of "River Grace--Red." Yet, when

the line is drawn, because of the unique power of gold, the line dominates the

whole. I try not to add anything to my paintings unless it changes the whole. In

fact, that's how I know that I have finished the work--when I give up because

anything I do will be superfluous. I think this principle applies to our lives.

We always try to have these Band-Aids on our hearts; we always try to fix this

and that, a little here a little there. What needs to happen, just as I try to

do in the painting, is a stroke, a line that changes our entire

being. Our entire selves will be made new, different. The prophet Ezekiel, with

God speaking through him, says "I will give you a new heart, put a new

spirit in you."

My wife experienced grace in this manner about ten years ago through a simple

understanding of the Ephesians verse I quoted before, "By grace you have

been saved." Before that she was like the man trying to climb up the silver

thread, afraid that it might break. She understood for the first time that grace

had nothing to do with that; it was something that God had already prepared for

her. Since it is God's grace, like the golden line, it will never change. So she

rested her heart on this truth that instead of trying to live up to a supposed

standard that God had set for her, she would invite him to live her life through

her.

I noticed a difference in her being. I noticed the way she treated the Bible

differently. She began to see it not as a book of law but as a love letter. So I

was surprised by this--I thought I always knew more than her. I used to always

try to quiz her about what she knew of biblical history although I did not for

sure consider myself a Christian. My wife had invited me to attend church with

her and, being a typical artist, I did not like going a church. An artist

dislikes anything institutional. I went just to please her. Once there, though, I

met many people my own age, who shared their struggles with me, but also

their passion and commitment to this Jesus of Nazareth. I understood commitment.

I used to measure people against their commitment to their identity, perhaps

because I was so proud of my commitment to my own art.

My commitment to my art was drawing me inward and I struggled with trying simply

to love. But these people seemed to have a balance of inward discipline and

outward love. One friend told me, "You know, Mako, you do have many

criticisms of the church and Christianity; some of what you say is true, but have

you looked, I mean really looked, at the person of Jesus Christ?"

I sat in a small apartment in The Twin Rivers of Tamagawa on a cold February

morning. I went back to my art and back to a "mentor" of mine from

college years, William Blake. I was reading that day, his last epic poem

"Jerusalem," William Blake's most consolidated work. In it he

synthesized ideas and aesthetic ideals that he had been developing all his life.

I waded through some 120 pages long, the culmination of his work and the work

that he was most proud of.

At the end of this poem William Blake, through his emanation Albion, who

symbolizes all searching humanity, comes to the cross of Christ. Throughout the

book Albion asks many of life's deep questions--I am sure, if you read it, your

questions are there. The accompanying engraving right next to it is a picture of

Albion with his arms outstretched, looking up. Of course, what Blake was doing

was showing that in order to understand the cross we have to imitate it in some

way.

Albion comes to the cross and asks, "Oh lord, what can I do, my selfhood

cruel marches against thee deceitful, to meet thee in its pride." And Jesus

replied, "Fear not, Albion, unless I die though canst not live, / but if I

die than I shall arise again and thou with me ... Wouldst thou love one who never

died for thee / or ever die for one who had not died for thee, / and if God dieth

not for man and give not himself eternity man could not exist, / for man is love

as God is love, / every kindness to another is a little death in a divine image

/

nor can man exist but by brotherhood". Notice the language of transaction.

What I understood that day, which changed my life and changed my art, was

this--we do not understand these heavenly words like grace or love or peace or

joy until they are shown to us. We learn by example. And the only way we can

understand this word of love which I really did not understand fully, was that

someone would go to the extent of dying for another to show us what love meant.

Love costs. Calvary's cross cost God's Son his life.

This language of transaction hinges on Albion's words, "My selfhood cruel

marches against thee deceitful." Just as I identified with the story of this man and the

silver thread, I identified with Albion, and as my

art became a treasure, something I wanted to hold onto, it enslaved me rather

than freed me. What was happening was that I didn't want to let go, to lose

control, even though my control was not over my life only over my works. I had

to be willing to be shown that I was marching against the Creator God himself.

To love is to die--it's a simple way of defining love. I found myself completely

surprised that these words of a 18th century poet and artist had exactly the

same message as 20th century Christians, those church friends of mine, were

trying to share with me. This parallel, this connection, this agreement had

profound significance for me--penetrated my heart. Something moved within me; in

my heart, my allegiance was then transferred from Art to Christ that day.

As I reflect on this today, using this theme of grace, my life parallels this

painting. I have come to understand something unique about grace. It is not

silver, it is golden. It comes into your life--in my case, almost invisibly and

I'm sure for some of you it comes as dramatically as in Paul's case. In my case,

I understood the word grace, and understood that this thread of grace was running

throughout history, and that Christ 2,000 years ago on that hill at Calvary was

thinking of me and that he wanted to show me how I could reconcile the schism I

found in my heart that resulted from a greater schism between my heart and

God's heart.

Paul writes in the book of Colossians of the Messiah. "He is the image of

the invisible God. The first born over all of creation. For by him all things

were created. Things in heaven and in earth, visible and invisible. Whether

thrones or powers or rulers or authorities, all things were created by him and

for him. He is before all things and in him all things hold together. For God

was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him and through him to reconcile

to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making

peace through his blood shed on the cross."

I realized as I prepared for this talk something about my Niagara experience

I've never realized before--why the experience was so haunting for me. When I

got married, I did not want more than one child for fear that I would not be

able to support children as an artist. I was afraid of losing control of my

life. But for us, having children meant in faith trusting God to provide, and

responding to God's grace poured out in our lives. We now have three children. I

have certainly lost control. You see, I would never have had the experience at

Niagara with C.J. apart from our decision to trust God with our lives. This

decision, like the origin of the falls, then a singular decision based on our

response to God's grace, now has literally multiplied to define my life in a

greater way. I would not have this exhibit apart from my grace experience. None

of these paintings would be here. Each painting, the gold, silver, precious

minerals, testify to God's gracious provision for us in these past years. The

extravagance of the materials used only contrasts the poverty of my heart.

Again, if I take the glory of the substance seen to be of my own glory, I know

my heart will be crushed. If I take on the glory of my children and my wife on

my own strength, I will fail miserably. I am like Jean Val Jean, whose life has

been touched by grace; my work of art are my candles. They are God's Images of Grace.

Copyright Makoto Fujimura. Used by permission.

The Extravagance of God

By Makoto Fujimura

The story of Jesus being anointed at Bethany by Mary is recorded in all four

of the gospels, revealing the importance and the impact the incident made on the

writers of the gospels. Mary, the sister of Martha and Lazarus (whose fame was

being raised from the dead by Jesus in the previous chapter), "took about a

pint of pure nard, an expensive perfume; she poured it on Jesus' feet and wiped

his feet with her hair. And the house was filled with the fragrance of the

perfume" (John 12:3).

Judas Iscariot vehemently objected saying, "Why wasn't this perfume sold

and the money given to the poor?" (vs. 5). And this event, the gospel of

Mark records, was the straw that broke the camel's back. After this incident, he

betrayed his master. The passion of this extravagant act provoked an equally

opposite, and ugly, emotional reaction. As one disciple devoted herself to the

master, the other betrayed him.

A pint of pure nard was worth about one person's wage for a year. In today's

terms it would therefore be at least $30,000 (depending on where you live of

course). No wonder that Judas objected to such "waste". If you saw

someone pouring such expensive perfume on another person, I think the natural

reaction would be to question "why?". Was the object of adoration

worth this amount of devotion? Was she crazy, deceived by a charismatic figure,

or indeed, as Judas claimed, foolish?

Artistic endeavors somewhat parallel this extravagant devotion. All the time and

money that goes into making someone proficient (let alone a master) Chopin

player are extravagant. Are piano lessons worth all the time and cost? In my own

work, I use such expensive materials, I often have to weigh what my family will

eat that week with what I can order for materials. Why do I use such expensive

mineral pigments and gold? Last month, I had the privilege of attending the

Glimmerglass Opera in Cooperstown, New York. I could almost hear these cost

questions reverberate in the wonderful production and set of this remarkable

opera house; Is it worth it to spend so much on opera when people are starving

to death elsewhere? The arts parallel this act of pouring the expensive perfume.

Is the expense justified in art? In order to answer this question, we must

answer not with "why", but "to whom". And it seems to me

that we have only two answers to this question of "to whom"; it's

either to ourselves, or to God. We are either glorifying ourselves or God. And

the extravagance can only be justified if the worth of the object of adoration

is greater than the cost of extravagance. The glory of the substance poured out

can only reflect the glory of the one to whom it is being poured upon. And if

the object of glory is not worthy, then the act would be foolish and wasteful.

Most of the time, unfortunately, even our best acts of "devotion" turn

out to be an instrument for worldly success and gain. Judas was an extraordinary

man with extraordinary gifts; he, along with the other disciples, healed the

sick, delivered people from demons, and preached the good news of the Messiah

(Matthew 10:4). He gave up everything to follow the Master. And yet, ultimately,

he thought Christ had come to reign on the earth, to give him earthly powers and

privileges. His heart ultimately deceived him as his master stepped closer and

closer to the cross; the cross that would strip Jesus, and his disciples, of all

earthly privileges and power. The only earthly possession Christ wore on the

cross was the very aroma of the perfume Mary had poured upon him. And Judas

betrayed the master for 30 pieces of silver; notably less than the worth of

Mary's perfume.

Often, what we think of as our adoration and offering to God turns out to be

false adoration and offering. The Bible is full of characters like Cain and Saul

who thought they were making good offerings to God, when in fact they were not.

Their offerings, and ultimately they themselves, were rejected by God. How do we

know that our offerings are acceptable?

One true test is that true adoration and worship is always God-initiated (in

response to what God has already done) and not self-initiated. Something comes

to you, surprising and life changing--transcending everything you thought was

possible. It may come in the form of an event or a person. But the content of

such a message opens your mind to the possibilities of God's existence and his

ever-reality. You are afraid and reluctant because such matters are too

wonderful and seemingly unbelievable. And yet, the adventure beckons you to leap

beyond yourself to a new domain, casting aside your comfort zone, your previous

definition of God. Such was Mary's reaction.

If your act of adoration is earning "points" with God, your actions

will not ultimately please God but only yourself, becoming a dull religious code

of ethics. No matter how hard you work, how much you sacrifice, you will not

experience the joy overflowing. On the other hand, the arts are a glorious gift

from God; and in the process of creation lies the joy of God's creative

heartbeat. Thus you will find in the creative process freedom and release; you

will find joy and a measure of greatness, whether you believe in God or not. But

if the offering is made to the Altar of Art and altar of self-glorification, you

will find, as I have, the glory of your own works to create a schism in your

heart. Your works, your ideals will only point to the double-mindedness of your

own motives and existence. There will be a gap between who you are and what you

create.

Mary had seen Jesus raise her brother from the grave. She also heard the master

talk about the punishment on the cross that he was to bear in Jerusalem in a few

days. I suspect she connected the two events together in her mind. There was a

direct correlation between her brother's life and her master's impending death.

If she did not understand this analytically, as her sister Martha would have

understood (John 11:27), she understood it intuitively. Her Master had to

suffer, because he was so willing to weep and intervene, not only for her

brother but also for her. He stepped into their domain, but as thankful as she

was, she also knew that her world was filled with falsehood and sin. Thus, as

soon as he chose to intervene, the glorious Prince of Peace had to become

disfigured because of the reality of sin and death; the Beauty had to become the

Beast. Every time Jesus healed and forgave, he stepped closer and closer to the

cross, the judgement of God. The cross should have been for you and me, the

Beasts trapped in the curse of our own doing; but Christ, the ultimate Beauty,

intervened and took the punishment for us. Pouring a $30,000 perfume upon his

feet is the least a Beast can do for the Beauty who loves us so unconditionally.

Jesus said after Mary's act of adoration "Leave her alone. Why are you

bothering her? She has done a beautiful thing to me ... I tell you the truth,

wherever the gospel is preached throughout the world, what she has done will

also be told, in memory of her" (Mark 14:6-9). What a commendation! What

hope these words give us to present day Marys like us. Because the sad truth is

that even if our offerings are made in pure adoration to the Father, and our

creative acts reflect him, our friends, our families, and our churches may not

fully comprehend our acts of adoration. Take heart ... God is for you and your

acts of pure adoration even if the world does not understand.

It is our prayer and desire that God will say that we have "done a

beautiful thing" for Him; both as individual artists and as a body of

creative people. Art that reflects God's grace and love will always accompany

his Message; Mary, the quintessential artist, has already paved the way for us.

Copyright Makoto Fujimura. Used by permission.

The HyperTexts

Even the materials and technique I use reflect both the transcendent and the

immanent. As many of you know I spent six and a half years in Japan studying the

technique of Nihonga, which is literally translated as "Japanese style

painting." I use materials and techniques developed over one thousand years

of Japanese paintings but using the visual vocabulary of twentieth century,

contemporary art. I import the materials from Japan--the works are all done on

paper--thin, hand-made paper. Some of them are stretched over canvases, some of

them over panels. For pigments I use mineral pigments, actually semi-precious

stone crushed, such as azurite, malachite, cinnabar pigments. These pigments,

when finely ground, become a lighter shade of color. Coarsely ground, they

remain dark and intense as on the left side of "Sacrificial Grace."

You can see on "Grace Foretold," the blue that is flowing from the

top--that is the azurite pigment.

Even the materials and technique I use reflect both the transcendent and the

immanent. As many of you know I spent six and a half years in Japan studying the

technique of Nihonga, which is literally translated as "Japanese style

painting." I use materials and techniques developed over one thousand years

of Japanese paintings but using the visual vocabulary of twentieth century,

contemporary art. I import the materials from Japan--the works are all done on

paper--thin, hand-made paper. Some of them are stretched over canvases, some of

them over panels. For pigments I use mineral pigments, actually semi-precious

stone crushed, such as azurite, malachite, cinnabar pigments. These pigments,

when finely ground, become a lighter shade of color. Coarsely ground, they

remain dark and intense as on the left side of "Sacrificial Grace."

You can see on "Grace Foretold," the blue that is flowing from the

top--that is the azurite pigment. I use them not just because they are beautiful, which they are, but because they

have this wonderful lineage. I use them because of the specific symbolism

attached to them. For me, mineral pigments have significance as symbols; they

symbolize God's spiritual gifts to people and the glories of the saints in the

Bible. In Solomon's temple these precious stones were embedded in the walls as

well as in the garments of the high priest. When you look closely at these

paintings you see that they have a peculiar surface--they glitter and shine.

Crushed minerals, therefore, symbolize gifts both from heaven and earth, and

point to my deeper struggle to return the gifts given to the Creator.

I use them not just because they are beautiful, which they are, but because they

have this wonderful lineage. I use them because of the specific symbolism

attached to them. For me, mineral pigments have significance as symbols; they

symbolize God's spiritual gifts to people and the glories of the saints in the

Bible. In Solomon's temple these precious stones were embedded in the walls as

well as in the garments of the high priest. When you look closely at these

paintings you see that they have a peculiar surface--they glitter and shine.

Crushed minerals, therefore, symbolize gifts both from heaven and earth, and

point to my deeper struggle to return the gifts given to the Creator. Grace comes to us both hidden and revealed. Like the golden line here in River

Grace (Red), it remains peripheral to us, often unnoticed. It may signify the

inconsequential, a small beginning of something new. We certainly do not

recognize grace enough in our lives. This gift of grace is like the air we

breathe or the light we see or the water we drink. Unless it's removed from us

we do not appreciate it enough. But when you do see grace, just like this golden

line, it dominates everything you see and it becomes a significant indispensable

part of the whole.

Grace comes to us both hidden and revealed. Like the golden line here in River

Grace (Red), it remains peripheral to us, often unnoticed. It may signify the

inconsequential, a small beginning of something new. We certainly do not

recognize grace enough in our lives. This gift of grace is like the air we

breathe or the light we see or the water we drink. Unless it's removed from us

we do not appreciate it enough. But when you do see grace, just like this golden

line, it dominates everything you see and it becomes a significant indispensable

part of the whole.