The HyperTexts

Dr. Joseph S. Salemi Interview

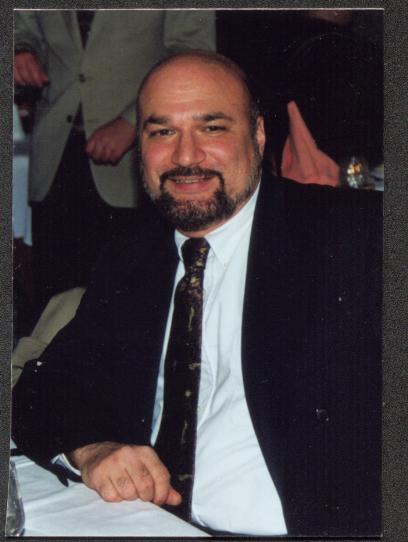

Dr.

Joseph S. Salemi is a widely published scholar, translator, and

poet. As a

translator, Salemi has rendered into English a wide selection of Latin, Greek, Provencal,

and Sicilian poems, and his scholarly work has touched on writers as diverse as Chaucer,

Machiavelli, Blake, Kipling, Crane, Ernest Dowson, and William Gaddis. He has won

several awards, including the Herbert Musurillo Scholarship, the Lane Cooper Fellowship,

and an N.E.H. Summer Seminar Fellowship. He was the 1993 recipient of the Classical

and Modern Literature Award for outstanding contributions to the combined fields of

ancient and contemporary literature, and was twice a finalist for the

Howard Nemerov Prize sponsored by The Formalist, a journal in which his work has

frequently appeared. He was also one of the 1995 winners of the Orbis Prize for

fixed-form poetry, sponsored by the English journal Orbis. Salemi is also

active as a journalist, writing on current academic issues and controversies for

Measure and Heterodoxy. He

is a grandson of the Sicilian poet and translator Rosario Previti. His

poetry books Formal Complaints ($5.00 plus $1.50 shipping) and Nonsense Couplets

($8.00 plus $1.50 shipping) may be ordered from him directly at: 220 Ninth Street Brooklyn,

N.Y. 11215-3902.

Michael R. Burch is a

much-published poet and the editor of The HyperTexts.

MB: Joe, I know you're a busy man, and I really do

appreciate your taking the time to do this interview. Can you tell our readers

what you've been up to lately?

JS: Well, my main work remains teaching, as has been the

case for the last forty-five years. I teach three classes in the Classics

Department of Hunter College, and two in the department of Humanities at NYU. I

also do private tutoring on occasion, so instructional labor occupies the bulk

of my time. As for poetry, I write it whenever I have a free moment. My new book

Steel Masks was published last year, and was just reviewed in The

Sewanee Review. I've been doing a good deal of translating recently, mostly

from the Satires of Horace and from Greek lyric poetry. I also contribute

a monthly essay to Leo Yankevich's The Pennsylvania Review, and have done

so since 2008. But my major task is the editing and publishing of

TRINACRIA, the

tenth issue of which will appear in October. That issue marks five continuous

years of publication.

MB: Joe, please tell us more about TRINACRIA. What in

heaven's name could have possessed you to launch a formal poetry journal on the cusp of

the 21st century? Are you a masochist, or is there a method to your madness?

JS: I felt that New Formalism was dissipating like a mist

cloud. Too many glassy-eyed enthusiasts were going on about how the movement had

to be "opened up" and "liberated" and "made relevant." And these types were

essentially diluting formalism's identity, both in the metrical and the

rhetorical sense. Some of this was deliberately done by persons who never liked

or trusted the movement in the first place, but most of it was simply due to the

irresistible undertow of the free-verse tide that surrounds us. I wanted a

magazine that was uncompromising in its commitment to real formal poetry, and

not to the vagaries of experimentation. God knows there are plenty of venues for

experimental work. What was needed was a journal that took an uncompromising

stand in favor of tradition. And no, I'm not a masochist. The work hasn't been

painful or onerous at all. Editing and publishing TRINACRIA has been a pure

pleasure.

MB: My friend Richard Moore once said that he was afraid

the new formalism would revert to the old stodginess. In my experience, having

edited The HyperTexts for two decades, there is a considerable degree of

stodginess in contemporary formalist circles, where many of the poets seem to

lack the courage to break from the herd. I think there is also an over-reliance

on "formulas," as if merely connecting the dots of meter, rhyme and form is the

be-all and end-all of poetry. But in my opinion poetry, to be an art, has to be

able to move readers, or at least capture and captivate their interest. Among

the poets you have published in TRINACRIA, are there any whose work might have a

chance to be read by future generations? If so, would you please share their

names and thoughts about them?

JS: Richard's worry about stodginess, while valid, was

misplaced. The real battle for New Formalism was to break free from the

stranglehold of free-verse habits of thought and composition. And if some

practitioners of the art are stodgy, that may have to do with their own limited

talents, and not necessarily with the art itself. The blunt fact is that there

are simply too many people today trying to be poets. Naturally in a situation of

that sort a good deal of the poetry in any particular movement is going to be

sub-par.

Your point about good poetry "moving" readers is fine in

the abstract. But when the great mass of our contemporary readership is

basically clueless about what actually makes for good poetry, then trying to

"move" them is both useless, and self-defeating for one's art. I have always

felt that worrying about the reactions of an external audience is the worst

possible thing that a poet can do, and I have expressed this view numerous times

in writing. Your task as a writer (if you're actually serious about the matter)

is to please your interior audience of values, criteria, and stylistic

preferences. Betraying them for the purpose of moving some anonymous pack of

readers (whom you can't know or identify in any case) is pointless.

I prefer not to single out any particular poets in

TRINACRIA for praise. I liked them all, or I wouldn't have published them. As

for the opinions of future generations—well, I simply am uninterested.

MB: Joe, you seem to be saying that readers need to

understand how poetry works in order to be moved by it. But I can enjoy good

music without knowing how it works, never having studied music. If I can be

moved by a song like "Danny Boy" and children who have never studied poetry or

theater can be moved by performances of Shakespeare's plays, doesn't that prove,

or at least tend to confirm, that knowledge of art has little to do with

appreciation of art?

JS: Naturally there is a naive appreciation of any art.

People can "like" a fine painting by Tiziano or Da Vinci, but still be

unaware of issues of perspective, foreshortening, palette, composition, brush

stroke, and all the other incidentals of a knowledgeable painter's craft. The

problem with saying that emotional reaction is all that really matters in art is

that it is vulnerable to the de gustibus non est

disputandum response. Suppose someone is moved by absolute garbage, or

tasteless trivia, or sheer ineptitude? Just look at some of the gushing praise

that is given at on-line workshops to poems that you and I both agree are

pathetic failures. And yet apparently such poems "move" some people.

Music is not a good example to choose, since music (as

Schopenhauer pointed out) is specifically directed to the will and to

instinctual urges. Savages can be "moved" by drumbeats and rhythmic cries. But

traditional formal poetry is a linguistic art, and therefore it demands a

certain rationality and verbal awareness and associative memory.

As for those children being moved by performances of

Shakespeare's plays—what in fact is moving them? It's not Elizabethan poetry, or

early modern English, or the manifold allusions to classical myth. What's moving

them is the mere fact of performance itself: the strange costumes, the action on

stage, the rough-and-tumble of fighting and swordplay, and a day off from

school. Don't mistake Joseph Papp razzle-dazzle for a real appreciation of

Shakespeare. I've taken many classes of students to see Shakespeare, and what

they get out of it is merely the enjoyment of surface phenomena of that sort.

MB: Joe, it sounds as if you're saying that most human

beings must be unable to appreciate the beauty of sunrises and sunsets because

they don't understand the physics involved. And what sort of reaction to beauty

can there be, other than an emotional response? Is there any intellectual reason

to believe that sunrises and sunsets are more lovely than overcast skies? Why,

when a rainbow appears in one of those overcast skies, does it seem like a small

miracle?

"Danny Boy" has lyrics, quite evocative ones in my opinion, even without the music.

I didn't say that an emotional reaction is "all" that matters.

Why do you speak so dismissively of children, I wonder?

When I was a child, I was fully able to appreciate poetry without any of the

trappings you mentioned. Without any formal training in poetry, I read poems

independently and I recognized the great poets by their unadorned words and my

emotional and intellectual response to them. Emily Dickinson said that she knew

real poetry by her physical reaction to it. Robert Frost, perhaps the greatest

strict formalist of recent times, said that poetry begins in delight and ends in

wisdom. Shakespeare himself wrote: "The poet's eye, in a fine frenzy rolling, /

Doth glance from heaven to earth, / From earth to heaven." Do you think they

were "naive" to believe there is more to art than following its brushstrokes?

JS: A sunrise or a sunset is not a literary artifact, Mike.

You're confusing natural phenomena with complex cultural creations that are the

product of thought, deliberation, and the remembrance of one's verbal

inheritance.

I did not speak dismissively of children. I simply pointed

out that they do not usually have the sophisticated appreciation of a text that

comes with age, learning, and experience. What's so upsetting about that? A full

and mature understanding of a literary text comes out of what I have called "a

literary sensibility"—that is, a sensibility that has been steeped in the

careful reading and long-nurtured appreciation of one's linguistic traditions.

Naturally children won't have that until they've gotten many years of reading

under their belt. And until they do, their reactions to works of art will be

essentially visceral. There's nothing evil about such a reaction, but there's no

need to canonize it into something wonderful.

Frost's remark about "delight and wisdom" is merely a

crackerbarrel American version of Horace's dictum from his Ars Poetica that

poetry's task is to "delight and to teach." As I argued with Robert Darling many

years ago, the dictum is purely a cover story, utterly unconnected with anything

that Horace does in his own poetry, and basically unconnected with how real

poets produce their poems.

You're putting words into my mouth by claiming that I am

suggesting that art is no more than "following brushstrokes." I never said that.

What you don't seem to understand is that there are many possible reactions to

beauty (or anything else, for that matter) other than an emotional one. As for

Emily Dickinson, she didn't say that her reaction to good poetry was actually

physical. She said that when she read something good it was as if the top of her

head were blown off. That was only a metaphor on Emily's part. She meant that

she had a complex inner experience of intellectual perception, critical

appreciation, linguistic fascination, and yes, affective response. That's light

years beyond the emotional gush that inundates us now.

MB: Joe, I am not "confused." I made the point that human

beings don't have to understand the source of beauty to appreciate it. If I

don't have to understand the physics of sunsets or the biology of songbirds,

then I also don't have to understand the mechanics of human art. I know very

little about music or painting, but I still appreciate great music and

paintings. I can't explain what makes women beautiful, but I sure as hell know

beautiful women when I see them. And I think Socrates would question how much

you really "know" about art: do you fully understand every aspect of the

physics, chemistry and biology involved? The universe is full of mysteries and

honest scientists admit that they still have a lot to learn. So if you

appreciate great poetry and art, and yet can't explain every aspect down to the

quantum level, you have helped prove my point.

I am not "upset" about what you said about children; I just

disagree with you. Richard Wilbur said, "I credit them with the brains and sense

of humor that they really do have." I agree with Wilbur. And having been a child

who read poetry independently, I can assure you that I got a lot more out of

what I read than an "essentially visceral" response. Young children have amazing

intellects. They learn much faster than adults. My childhood response to great

poetry was both emotional and intellectual.

Frost, a man who knew the meanings of words and used them

precisely, said that poetry begins in delight, not that it delights and

teaches simultaneously. He also defined poetry as an expression of emotion: "A

poem begins with a lump in the throat; a homesickness or a love sickness. It is

a reaching-out toward expression; an effort to find fulfillment. A complete poem

is one where an emotion has found its thought and the thought has found words."

Wordsworth said something very similar: that the source of poetry is recollected emotion.

Wilbur said in an interview that the poems of Frost's that he loves best are his

emotional, lyrical poems. Sidney said that his Muse told him to look in his

heart and write. Shakespeare and Dickinson were obviously talking about the

emotional aspect of poetry as well. Dickinson said, "If I read a book and it

makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel

physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry." She

actually used the word "physically." These major poets knew that great poetry is moving. If you appreciate great poetry

without knowing this, you have just helped prove my first and second points.

JS: Arguing about "the physics, chemistry, and biology" of

a poem (or one's reaction to a poem) is meaningless. A poem is a cultural and

linguistic artifact. It can't be examined like a biopsy slide under a

microscope. And neither can the intellectual response of a reader.

No one is denying that children have brains and a sense of

humor. But putting their untutored reaction to a literary work of art on the

same level as that of a trained adult reader is utopian. Look—when I was a kid

(about seven or eight years old), one of my favorite poems was John Masefield's

"Spanish Waters." The main reason I liked it was because it was about buried

treasure, a subject that fascinated me back then. I could read the poem, and I

understood its basic gist, and I enjoyed its rhythmic flow. But there was much

of it that was utterly beyond my ken. My mom had to go over it with me line by

line, explaining difficult passages and recondite vocabulary. How else could I

understand a line like:

Longing for a long drink, out of silver, from the ship's cool lazareet

or the line "Jewels from the bones of Incas, desecrated by the Dons"

or a phrase like "bezoar stones from Guyaquil"? Or how

would I know that the name of the beach in the poem, Los Muertos, meant "The

Dead"? All of this had to be carefully explained to me by my mother. She told me

about inversions, and the poetic license that allowed Masefield to say

"lazareet" instead of "lazaret," and who the Incas and the Dons were. Without

her adult understanding and explanation, my reaction to the poem would have been

utterly maimed and superficial.

You end your question by quoting a raft of authorities:

Frost, Sidney, Wilbur, Wordsworth, et al. Why should that prove anything to

anybody, Mike? As a matter of fact, famous poets are notoriously undependable

when it comes to giving explanations for aesthetic practices, whether their own

or anyone else's. Such explanations are always after the fact, and they are

frequently self-serving. Name-dropping doesn't constitute an argument.

MB: Joe, I don't agree, but rather than beating a dead

horse, let's move on to your poetry. In my opinion, your best poem is "The

Lilacs on Good Friday" and I also especially admire "The Missionary's Position."

Please tell us how you came to write those poems: their inspiration, how your

faith informed them, and anything else you care to share with our readers.

JS: Yes, we can agree to disagree and move on. I know that

you like the missionary poem, so I'll start with that one. It was written many

years back, and I can't fully recall the circumstances of its composition, but

it's very likely I wrote it for submission to the Howard Nemerov competition

that used to be run by Bill Baer's The Formalist magazine. I produced a

large number of sonnets just for that contest. As for its subject matter, it is

related to my dislike of any sort of proselytizing and evangelizing. I have a

viscerally negative reaction to anything that is hortatory or preachy, or that

has the aim of converting strangers to one's way of doing things. So I imagined

a missionary speaking and defending his successful attempt to convert savages to

Biblical precepts. I tried to show how the missionary did understand that he had

in fact complicated and wounded the psychic lives of his converts, but how he

also refused to admit that his actions were bad or harmful. I close the sonnet

with him saying that the Word of God is "better endured in grief than left

unheard." That to me is the evil side of evangelization—the notion that even if

what we are bringing to you is painful and upsetting, it's nevertheless "good"

for you. People often read that sonnet as an anti-Christian poem, and its

incidental imagery supports such a view, but in fact I meant it more as an

anti-liberal poem. The title, of course, is comical and ironic—it alludes to the

practice of many missionaries of compelling their native converts to have sex

only in the face-to-face position, as if the position one takes in coitus had

some sort of religious or moral significance.

The second poem ("The Lilacs on Good Friday") is much more

complicated in both its subject matter and its compositional motivation. I wrote

it around 1997, at a time when my father was seriously ill, and the sense of

impending mortality was very heavy in my mind. The poem's basic armature is a

description of some very old and tall lilac bushes in my parents' garden in

Woodside. I have always associated lilacs with Easter and the Resurrection,

simply because they tend to bloom around that time of year. What the poem does,

in a dozen quatrains, is to conflate a memory of Christ's Passion, death, and

impending burial with images of falling flowerets and the beauty of lilacs, as

well as alluding to the gardens of Eden and Gethsemane. I also make use, via

concise translation, of the versicle and response from the Office of the Holy

Cross (Domine, labia mea aperies / Et os meum annuntiabit laudem tuam),

when I write "Open my lips, O Lord, and let my tongue / Announce thy praises".

So the poem is a complex meshwork of fear, sorrow, prayer, and concern for the

impending death of a loved one, placed in the family setting of a garden, on the

most sacred of days for a Roman Catholic.

MB: One might say that taken together your poems contrast the

good and bad of Christianity. I know from essays and other poems you've written

that you particularly dislike American puritanism and protestant evangelism.

Those are things we can certainly agree about. Having grown up attending

evangelical Christian churches that churned out bizarre ideas—sex is "evil," the

earth was created 6,000 years ago, Christians must support Israel in order to

escape the "tribulation"—well, in this case familiarity has bred contempt. The

last idea seems likely to ignite WWIII, especially if another "born-again" moron

like George W. Bush occupies the White House at the wrong time. And yet most

contemporary poets seem to lack the wisdom (or is it the guts?) to call

right-wing churches and their religion-addled congregations what they so clearly

are: perhaps the greatest threat to continued human existence in the history of

our planet. If writers oppose the evil collusion of American neocons and Israeli

war hawks, the writers are accused of being "anti-Semites" and "intolerant."

Have you ever been attacked in literary circles for calling a spade a spade?

JS: I've spent a great part of my literary career being

attacked by all sorts of persons. It's what you might call an occupational

hazard of anyone who is a right-wing conservative Roman Catholic white male.

It's true that I have a strong distaste for both American puritanism (the

half-assed idea that the United States is a "city upon a hill" and somehow

morally "exceptional") and for Protestant fundamentalism. This distaste began

with my reading of H.L. Mencken, and was reinforced by both Samuel Butlers (the

author of Hudibras, and the later novelist who wrote The Way of All Flesh). But

this crackpot American idea is represented not just by those conservative

Protestant sects that you dislike, but also by contemporary liberalism. It's not

just pro-Israeli neocons who are trying to force their will on the world. It's

liberals in general, with their insufferable need to make the planet safe for

equality, feminism, gay rights, democracy, and all their other pet causes.

American liberals are now in full imperialist mode, ready to go anywhere in the

world to impose the liberal worldview and agenda on recalcitrant and benighted

populations. Hillary Clinton is a horrifyingly authoritarian bitch, and her

presidency would be as warmongering as Hitler's Third Reich.

I agree with you about one thing: if stupid evangelical

Protestant churches have their way, and encourage Israel to demolish or move the

mosque on the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem in order to rebuild the Temple of

Solomon and thereby usher in the Second Coming, it will ignite World War III. It

will happen just as surely as World War I was ignited by a little tubercular

Serb assassin in Sarajevo in 1914. It's amazing how fixated on absurdities some

of these evangelicals can be. But remember this, Mike: evangelical Protestants

and American liberals share the same political and ideological DNA, in their

itch to dictate and control. They are "sisters under the skin," as Kipling might

have said.

MRB: I don't see anything wrong with making the planet safe

for equality, feminism, gay rights and real democracy (i.e., a system in which

everyone has the same rights and protections). To me those are admirable goals.

I think there are obvious problems when groups demand special privileges and

work through the political system to get them. But who, pray tell, has ever

demanded more special privileges in the United States, than white conservative

men? Are you, perhaps, like a Great White Shark accusing dolphins of being too

aggressive when feeding? But getting back to your poetry, I understand that you

once wrote free verse. Do you still write free verse, or did you make a clean

break with non-formal poetry? In either case, I'd like to know the reasoning

behind your decision.

JS: I'll ignore your tu quoque fallacy and address the question of free verse. No, I generally

don't write free verse anymore, except for short squibs or notations. If I like

what I have done, I may develop it into a formal poem of some sort. But as to

why I largely stopped writing free verse, the answer is simply that it was

preventing me from being free. I couldn't do the best work that I could do if I

had to pay attention to all the prissy little strictures of modernism and its

soul-choking reticence. We've discussed this before, and I recall you saying

something like "Not even the modernists followed their silly rules about how to

compose poetry." I mean, Jeez... just look at the absurd restrictions that the

free-verse mentality imposes on its practitioners: no adjectives, no abstract

nouns, no syntactical inversions, no obsolete diction, no direct appeals to

sentiment, no rhetoric, no tropes or figures, and the most asinine of all, from

the New Jersey pediatrician: "No ideas but in things."

When I tried to write poetry that way, I was strangled! It

was like trying to do an oil painting while holding the brush in your teeth. The

poet Henry Weinfield once said to me that modernist free verse was essentially

New England puritanism trying to assert its hatred of the beautiful by paring

poetry down to a skeletal structure. And I think Henry was quite correct. Much

of the impetus to free verse, apart from Whitman, came from a surreptitious and

half-hidden dislike of verbal fullness and richness and abundance.

There's nothing intrinsically wrong with free verse, and if

people want to go on producing it that's their business. But I think thoughtful

persons should recognize that at this point in history free verse is an

aesthetic dead end, like the abortive English attempts at classical quantitative

verse in the sixteenth century. It was cute and interesting for a while, but

hey, let's move on.

MB: Joe, I agree with you about the errors of what you call

the "free-verse mentality." I think readers abandoned modern poetry in large

part because so many poets became disciples and evangelists of irrational

literary dogma like "no ideas but in things" and started producing imagistic

post cards rather than real poetry. But I have lurked on formalist forums and

heard the worst ideas of modernism being trumpeted: "fear abstractions," "avoid

sentiment," and so on. The real problem, I believe, is groupthink. Formalists

seem to be as susceptible to it as other groups, believing things that aren't

true rather than examining the evidence and thinking independently. To me,

strict formalists are like the people who once believed the earth is flat, and

wouldn't travel far from land. When more venturesome sailors finally

circumnavigated the earth, rather than accepting the evidence that the planet is

round, the shore huggers noted that some people died on the groundbreaking

journey, and went back to believing in a flat earth because that seemed safer to

them. But surely we should judge a movement by the successes of its best

artists, its Magellans, since none of the failures matter in the long run.

Didn't poets like Walt Whitman, T. S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane and e.

e. cummings prove that there really is a round globe rather than flat earth? If

they wrote masterpieces—"Leaves of Grass," "The Love Song of J. Alfred

Prufrock," "Sunday Morning," "Voyages," "i sing of Olaf glad and big"—how can

formalists claim that the work is merely "cute and interesting," and that the

world is once again flat, or will be soon?

JS: Mike, I never would deny that there have been

masterpieces of free verse, especially by the persons whom you mention. No doubt

about it.

I've acknowledged that truth many times in my writings on

aesthetics. In the hands of a genuine master, any form (or lack thereof) is

capable of presenting us with something great. The real problem is what you have

just mentioned—namely, that even on so-called "formalist" websites and

discussions rooms, you hear the participants spouting the same old drivel about

"no abstractions" and "no adjectives" and "no ideas but in things" and all the

rest of the orthodox propaganda of the Free Verse Establishment. As I wrote many

years ago, people of this sort have what Franz Fanon would have called

"colonized minds." They think they have broken with modernism and free verse,

but they haven't. Not at all. They are still mentally enslaved to free-verse

habits of thought, and received modernist assumptions. As I tell students in my

poetry class (when I get to teach it), there's no goddamned reason to write in

iambic pentameter if deep down you are still Walt Whitman and Carl Sandburg.

You've called it "groupthink," and that is absolutely correct. When Dana Gioia

speaks disparagingly of the "anti-modernists" in the ranks of the New Formalist

movement, what does that tell you? Since when does the putative leader of an

aesthetic movement try to anathematize its core constituency?

MB: Joe, I think you have the more mature approach when it

comes to evaluating the better free verse poets. It's beyond silly for other

formalists to pretend that the best free verse poets didn't produce

masterpieces. And it's equally silly for them to pretend that poets like Eliot

and Stevens were closet formalists. They both knew what they were doing, and

why. Now the bar has been raised, so all poets, from the strictest formalists to

the least inhibited free verses, have to rise to the challenge. I think Hart

Crane understood that, when he read Eliot's work. I remember your friend the

formalist poet Alfred Dorn writing an appreciative essay about Crane that

appeared in Pivot. Richard Moore was an advocate of perfect rhymes who

admired the "extraordinary delicacy" of Walt Whitman. If they saw free verse as

the Devil, at least they were willing to give the Devil his due. Or perhaps they

had a broader, more embracing vision of poetry. But in any case, poets can't

achieve immortality by sticking out their tongues at their betters. Would you

agree that formalists need to write poetry that rivals the work of poets like

Eliot, Stevens and Crane, if they want to be taken seriously, rather than

vacillating between burning them at the stake and trying to adopt them?

On the other hand, I think Dana Gioia probably has good

cause to speak disparagingly of the "anti-modernists" in the New Formalist

ranks. Why not take the best the older tradition has to offer, and the best

modernism has to offer, then move smartly forward using a "best of both worlds"

approach?

JS: Well look—you've asked a great many questions there and

they involve a number of suppositions that I don't necessarily accept. First,

about Alfred Dorn—he was profoundly influenced by the example of Hart Crane. But

the thing that most moved Alfred was not so much the free verse style as the

sheer rhetoric of Crane. In fact, when Crane was depressed he often dismissed

his own work as "just rhetoric." And yet that rhetorical fire—that flamethrower

of linguistic power that Crane could handle so well—was precisely the thing that

got Alfred Dorn going. And of course when Alfred started writing he did produce

a lot of free verse, much of it quite good. Later on, as a result of his

scholarly training in Renaissance literature, Dorn moved towards more formal

work.

As for "raising the bar," that's merely a metaphor, and

metaphors don't always function well in analysis. If free verse poetry and

formal poetry are qualitatively different, and if they work by using rules of a

singularly different nature, then neither one can be used as a yardstick for

judging the other. It's a peculiarly bad habit of contemporary persons that they

are always trying to create a synthesis or a union or a harmony where no

essential synthesis is possible or desirable. It's this insufferable "best of

both worlds" mentality, and it makes for crappy poetry.

Nobody is "sticking his tongue out" at good free-verse

poets or their poetry. Some of us are simply saying that we want to do our own

thing, and not have to pay obeisance to an aesthetic that we find uncongenial.

We don't ask free-verse types to write sonnets or villanelles. We ask the

reciprocal favor of them that they just leave us alone. Is that too much to ask?

No, I absolutely DO NOT agree that formalists "need to

write poetry that rivals the work of poets like Eliot, Stevens and Crane, if

they want to be taken seriously." Frankly, Mike, that is an absurd proposition.

No poet of any school or movement or persuasion has to do anything at all! The

poetry world isn't a boot camp where recruits take orders. Poets can do whatever

the hell they like or find pleasing. And when you say "to be taken seriously,"

the immediate question I would ask is this: "Taken seriously by whom? Who

exactly do you have in mind as the arbiters of proper composition?" Your

question suggests that there is some sort of privileged group of chosen judges

out there whose opinion all of us have to take into account when working. That

sounds pretty illiberal to me.

As for Gioia, he's doing his level best to make New

Formalism socially acceptable and establishment-friendly. I loathe that approach

and attitude. Dana is a nice guy and a capable poet, but he is perfectly willing

to write a great many good formalist poets out of the history books if he feels

that they are not easy to fit into the in-crowd of po-biz orthodoxy. But let's

not get into personalities.

MB: Joe, I certainly don't have a problem with poets or

editors who have a "formal poetry only" policy. But I think poets are clearly in

a competition to be read today and in the future. Would Shakespeare be

Shakespeare if he wasn't widely read? Shakespeare knew that in order to achieve

immortality for himself and his subjects, he would have to write poems that

continued to be read after his death. If formalists can't write poems as

compelling as those of the better free verse poets, readers will stop reading

the formalists and their work will wither on the vine. And what good are poems

that are unread and thus forgotten? They die along with their authors. I seem to

remember you expressing a concern, once, about preserving information. One way

to do that is through stellar poetry and other forms of art. But when you're

gone, if no one reads your poetry, in what way is anything preserved? Don't you

and other formalists need readers just as much as Shakespeare did?

JS: Mike, you've got it completely backwards. You don't

write poems in order to be read. You write poems that deserve to be read.

That's a crucial difference. The intrinsic quality of a work doesn't depend on

its readership, or lack thereof. As far as we can see, practically no one read

the Pearl Poet in his own day, and he had to wait half a millennium before he

was rediscovered and published widely. By then his medieval dialect was opaque,

and his poetic greatness appreciated only by a handful of scholarly readers. But

according to your argument he didn't win the competition for general mass

readership, and is therefore a failure. That's an argument for a car salesman or

an advertising agent to make, not a serious appreciator of literature like

yourself.

Moreover, you're still comparing apples and oranges when

you go on about some sort of competition between free verse and formal poetry.

As I said above, they attempt different things, and have to be judged by

criteria other than market-share. Sure, everybody wants to be read. But if

audience satisfaction is one's main concern, I'd seriously advise a person to

give up poetry altogether, and start a new career as a designer of computer

games. That's where the big audience is.

And let's be perfectly frank: I doubt that even "the better

free verse poets" are read by many more people than the captive-audience

students who are assigned to read them in college. Indeed, many of these poets

remain in print solely because of pre-semester faculty book-orders. How many

copies of Wallace Stevens (a brilliant poet, to be sure) would be sold if it

weren't for the artificial market sustained by English departments nation-wide?

Face it—poetry is a boutique art, or to put it more bluntly, a mere pimple on

the derriere of modern mass communication. There really isn't anything out there

for poets to compete about.

MB: Joe, I agree with you about the need for quality,

absolutely. But large numbers of people read Wallace Stevens voluntarily,

especially now that his work is available on the Internet. And if no one was

reading the Pearl Poet, he would be an entirely dead poet. If only a few

specialists are able to read his work today, he is on life support, compared to

the major poets. However, a superior translator might make him popular with

larger audiences. Sometimes poets are “resurrected” after their deaths. For

example, I have been working to revive the readership of

Anne Reeve Aldrich, because I think she rivals Emily Dickinson in her best poems.

(You’ll be happy to hear that Aldrich was a formalist.) And I have done

translations of Anglo-Saxon poems like “Wulf and Eadwacer” which are popular

with readers, receiving thousands of page views per year. But without readers,

poets and their poetry are dead, and I think that’s a fate formalists now face

en masse unless they can raise their games in this very stiff global

time-space competition. So once again, we’ll have to agree to disagree. But I

truly appreciate your time, and I commend you for your good work and results

with TRINACRIA, and for poems of yours that—thanks to their quality—have a

chance to be read in the future.

JS: Well, the problem is that it is difficult to compete with institutionalized

idiocy. I mean, consider this: the last issue of Poetry had a truly

mind-boggling essay by Peter Quartermain that essentially said (once you

negotiated your way through the jargon) that rationally explicable and

discursively coherent poetry is just not as exciting or valuable or real as

poetry that presents itself as a "happening" or an "event." In other words, a

good poem is simply something that occurs, like bird droppings on your patio.

When you have that kind of stupefying anti-intellectualism published in the

premier American journal for verse, what hope is there? The notion that poems

just happen, and that they are essentially inexplicable experiences of our

linguistic condition, is appalling in its consequences for the composition of

poetry, its reception, its teaching, and its connection to any world of

reasonable verbal communication. There's no sense trying to talkŚmuch less

competeŚwith an approach of that nature. But my view is the minority view these

days. In any case, I'm grateful to you, Mike, for giving me the chance to speak

at length here. Many thanks.

MB: Perhaps institutionalized idiocy is what one should expect, when the inmates

take over the asylum. It's hard to imagine the editors of Poetry

publishing William Blake, Walt Whitman or Emily Dickinson, and that makes we

wonder about the journal's title. Is it false advertising? But I have a feeling

the poetic cream will rise to the top in the end, and there are some of us

trying to make that happen sooner rather than later. Joe, while we disagree

about many things, perhaps we agree on the most important thing as editors,

which in my mind is publishing the highest quality poetry with discrimination,

but without prejudice against honest human sentiments, unconventional ideas and

(for God's sake!) modifiers. Once again, thank you so much for your time.

The HyperTexts